It was for a later generation to call the economic meltdown of 1930s the Great Depression. At the time people in the Texas Hill Country called it a panic, a pain in the arsch, or just plain old hard times. Whatever you call it, the depression smothered the area like a wet blanket. It was optimism, determination and a quirky sense of humor that helped the people of the Hill Country survive those difficult times.

In the beginning the fall of Wall Street was of only passing interest to the Hill Country. That’s because the people here had few connections to the nation’s business and financial network. Banks were privately owned and uninsured. Few people had stocks, bonds or retirement accounts.

The region was geographically and culturally isolated as well. Travel in any direction was an adventure. Roads were crude. There were few bridges and no pavement in the Hill Country in 1930.

For those citizens fortunate enough to own automobiles a trip from Fredericksburg to Johnson City took hours – if roadways and low water crossings were passable. A trip from Fredericksburg to San Antonio, over 70 bone-jarring miles of bad roads, took most of a day, one way, under the best of conditions. Model T Fords, not equipped with fuel pumps, climbed Stieler Hill in reverse to keep gasoline flowing from the fuel tank to the carburetor.

The railroad scratched and clawed its way over, around and through the hills to Fredericksburg in 1913, but travel by rail was surprisingly unreliable. Washouts, rock slides and derailments kept the train out of commission for days at a time.

The difficulties of travel kept this part of the Hill Country isolated and off limits to all but natives and the most determined of travelers. Migration in and out was limited. The area retained a strong European flavor in attitudes, customs, folkways and language. Young people learned English at school, but German remained the dominant language in most homes.

Because Hill Country people were so isolated, there was a level of self-sufficiency here that was uncommon in 20th century America. Citizens produced most all of life’s necessities, and many luxuries as well. They butchered their own beef, goat and venison. They baked their own bread, churned their own butter, turned their own ice cream, made their own wine and cured their own tobacco.

But if this self-reliant and secluded place didn’t face the depression’s full impact is was also because life in the Hill Country was tough already. Few homes had electricity in 1930. There were precious few telephones or flush toilets. In the age of radio there were few radios. In Fredericksburg, water wells and outhouses were scattered all over town, often in dangerously close proximity to one another. A bacteriological examination of Fredericksburg drinking water in early 1932 showed sewage contamination in water wells and cisterns.

Life out in the countryside was especially difficult. Many farmers still plowed with mules because they couldn’t afford tractors. The lack of electrical power meant that every chore was done by hand. Robert Caro in his Lyndon Johnson biography Paths to Power described rural life around Stonewall in the early 20th century as “out of the Middle Ages.”

Rural women spent hours kneeling over rub-boards, the strong lye soap burning the skin on their fingers. After clothes were washed and dried, women took out the wrinkles with heavy flatirons that had to be continually carried back and forth to the wood stove for reheating. For many women the only thing worse than the drudgery of hard physical labor was the loneliness of a life in the middle of nowhere.

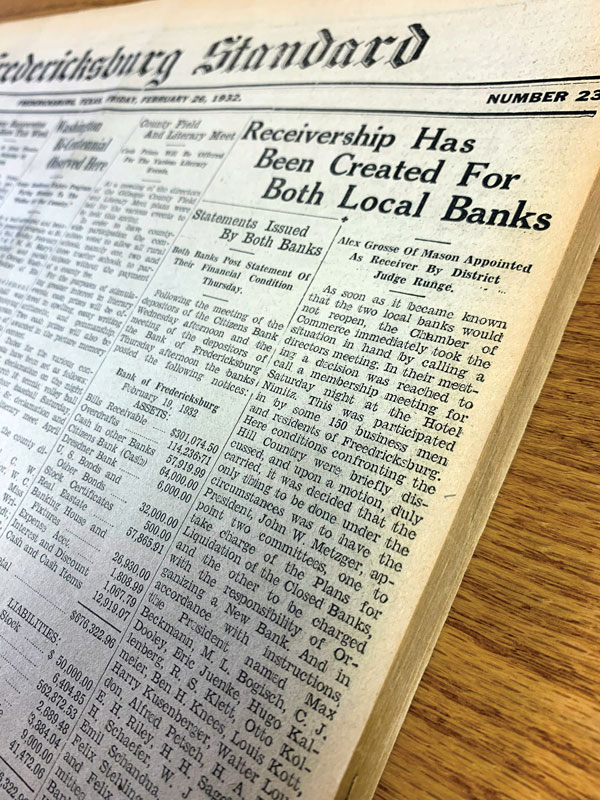

The economic news was not encouraging in the first two years of the depression, but life in the Hill Country trudged ahead pretty much as before. Then in early 1932 reality hit. On February 19th both banks in Fredericksburg closed without warning. Neither reopened. Life was never the same after that.

Bank closures caused a loss of faith in the banking system and a contraction of the money supply. The Palace Theater in Fredericksburg shut its doors for a time because no one could afford a ticket. Some Hill Country schools paid teachers in script or promissory notes. Grocery and mercantile stores extended credit for a year or more until cattle sold or crops came in. H-E-B grocery stores, with roots in Kerrville, had some anxious moments. Thirteen banks in which Howard Butt was a depositor failed in a year – four in one day.

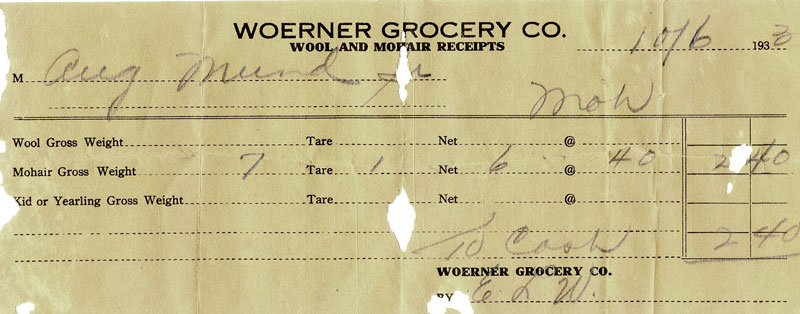

The price of cotton dropped from 22 cents a pound to 8 cents. Mohair sold for 7 cents a pound and had a hard time selling even at that piddling sum. Eggs went for 8 cents a dozen.

Even Cupid was a victim of the depression. Gillespie County Clerk Albert Klett’s office reported that although 1932 was a leap year and a full day added to February, his office issued only one marriage license for the entire month. Meanwhile the Fredericksburg Standard reported that “the stork was busy as usual” while “the grim reaper has also asked his average toll without regard to commercial situation.”

When President Roosevelt took office in March 1933, he planned to energize the nation’s economy by stimulating consumption. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) and other New Deal agencies made money available so that local governments could employ workers and pump some money into local economies.

Most Hill Country citizens saw federal work relief efforts as a good thing and a reason for hope, but others inevitably thought the New Deal went too far and lashed out at a government that paid workers for standing around and doing nothing. On the opening day of deer season a sign along a Mason County road read “Don’t shoot until the deer moves. It might be a WPA worker.”

While government programs helped needy citizens, in the long run it was the resiliency of the Hill Country people that pulled them through. They were down but never out. They looked long term. They knew from experience that life ran in cycles. Their history of isolation, stubborn self-sufficiency and “making do with what they had” served them well during the difficult days of The Great Depression.

When the banks in Fredericksburg failed and cash money was scarce, businesses reverted to the barter system. Keidel Drug Store in Fredericksburg took eggs and chickens for medicine. Then citizens and businessmen pooled their money and started a new bank. Fredericksburg National Bank opened on April 6, 1932.

Even in the depths of the depression, the people of the Hill Country held their celebrations of life. Weekend dances, county fairs, schutzenfests and saengerfests continued as before. Friends got together to bowl 9 pin or to play pinochle and skat. Most everyone shared what they had. If someone had 3 bottles of beer, 6 people got together and had a party.

Slowly conditions improved, especially after the Rural Electrification Administration (REA) strung electric wire all through the Hill Country. As the economy recovered Hill Country families, now equipped with electric power, bought refrigerators, electric irons, washing machines and water pumps. Quality of life improved dramatically. In 1930, 2 percent of Hill Country homes had electricity. By 1960, 2 percent didn’t.

Strands of gleaming silver wire, looped from pole to pole through the sparsely populated hills and valleys, along with improved roadways and concrete bridges, symbolized hope for the future and helped break the paralyzing grip of the Great Depression. The people of the Hill Country could relax for the moment until the day their steely optimism and steady determination were needed once again.