A diverse smattering of people meandered into the arena at Crider’s, passing through a gate where the words “It’s Time to Rodeo” were welded in perpetuity. Just beyond the entrance, two young girls with long side braids sat horseback and carefully ate snow cones.

Every Saturday night from Memorial Day to Labor Day, Crider’s, located near Leakey, draws a crowd. It’s a beloved tradition for many — locals, as well as those with summer houses in Hunt, touristing city mice, and my favorite genre to observe, the off-duty camp counselors and local teens who I saw gathering in heartening vignettes around every corner.

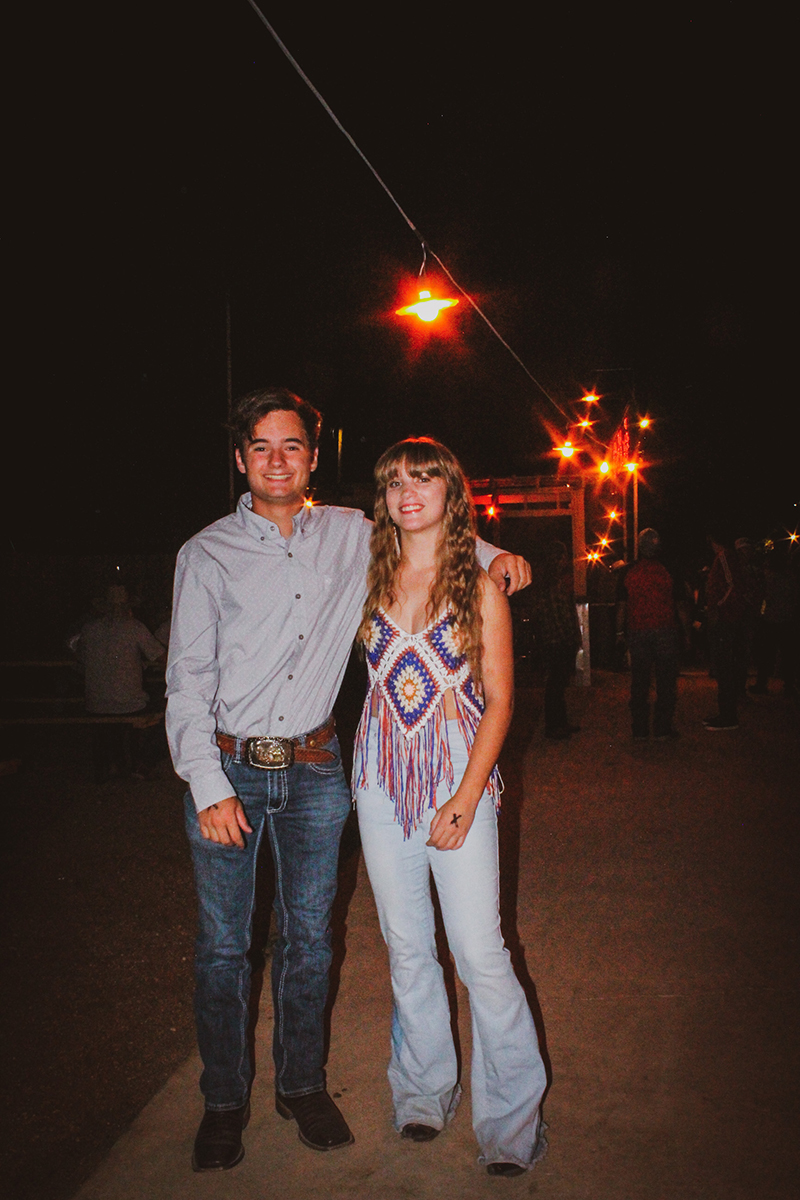

If these kids had cell phones (which I’m sure they did), they weren’t staring at them, and instead, they leaned on fences, sat on tailgates, and migrated from rodeo bleachers to starlit dance floor with a carefree gentleness that sometimes seems generationally scarce. There were tables of young boys with braces, stiff cowboy hats, and western shirts — some with an unassuming check print, and some with a delightfully 1990s pattern and an equally loud belt to match. Girls had on boots and bellbottoms, a resurfaced jean cut very fitting to the Texas of it all.

I wanted to meet the family behind it all and waited for Tracy Moore at one of the tables in the bar, which functioned as a makeshift office. The barn wood walls were adorned with relics from a generation before including tools, at least one stuffed aoudad, and an impressive display of well-worn cowboy hats that belonged to Tracy’s father-in-law. It was several hours before official show-time on the opening Memorial-Day weekend, and Tracy took the opportunity for a breather.

“Would y’all like a water or a soda?” she hollered from around the corner where she fetched a bottle of water for herself. Despite the excitement and lingering punch list for upcoming events, she was friendly and relaxed.

Her son, Dakota, and husband, Bill Moore, pulled up a chair, as Clayton, Dakota’s 3-year-old son, poked around the corner. Not long after, Clayton’s mom, Madison, also took a seat. “You ready?” Tracy asked Madison, who would later be bartending. “You better have on good shoes, that’s all I have to say,” she said smiling. I’d like to think the Moore family gathered on account of my pleasant company, but truthfully, they probably just knew it was going to be the last time they would sit until 1 a.m. when the last dancers were scooted off the dance floor.

Tracy oversees the café and dance, while Dakota helps with ticketing and security. Her oldest daughter, Megan, and her husband run the rodeo. It seems all the Moore kids help run the website and social media. Once the kids were older, Tracy’s husband Bill (who ran the rodeo for 17 years) got back involved operating an over-the-road entertainment trucking service. He’s toured with the biggest of names including The Rolling Stones and U2. “I’ve lived a lot of lifetimes,” he explains. Later this summer Bill leaves for a tour with Elton John.

Crider’s Dance Hall has been around since 1925, first started by Walter and Audrey Crider, Bill’s grandparents. Walter was the Hunt School Board President and the first-ever Crider’s gathering was a school fundraiser. They rented a portable wooden floor for folk dancing and “threw a barbeque and dance down by the river,” as Tracy put it. Over the past 96 years, the Crider’s spirit has remained the same, but the place itself has evolved. In 1932, the Guadalupe River swallowed its banks, wiping out most of Hunt, and forced the dance to move across the road, to the Crider’s General Store. (The original general store sign, bold black lettering on white wood, hangs in the current bar.) During World War II, the dances stopped and then resumed back across the street (riverside) with a permanent dance floor and a new rodeo arena. In 1993, a fire burned down the bar and damaged nearly half of an iconic oak tree that was at the center of the patio. In 2017, Bill’s mother Laverne Crider Moore passed away. She was buried in January, and that March, the iconic oak died for good, a withering so tragic it made the cover of the Hunt newspaper, the West Kerr Current.

This year, there is a new property fence and the picnic tables are refurbished with metal bases. “It’s been a long couple of weeks,” Tracy tells me dragging out the long for emphasis, “It really has been a long couple of weeks. We’ve got a lot done.”

That’s likely a familiar sentiment for Crider descendants at the onset of every summer season. Tracy, who is a Northern Michigan native and “absolutely hated country music when [she] moved here,” met Bill on a blind date at Mamacita’s restaurant in Kerrville, and has since adopted the Crider ethos as her own.

Tracy and Dakota laugh when asked if anyone ever causes trouble at the dances. “When we have issues with security, people are like, ‘I want to speak to the manager,’” Dakota chuckles, “And I’m like, are you sure? Are you sure?! I’ve been speaking with her for 29 years and I still lose those fights.”

We’re all laughing now, and I’m reminded of Tracy’s impression of Laverne Crider Moore, Bill’s mother. “She was just as sweet as could be, but pretty tough.”

The show at Crider’s starts at 8 p.m., and as if on cue, the restorative evening breeze descends with just enough vigor to carry a sweet whiff of rodeo dirt. The bleachers face the river, and the bluff on the opposite bank warms to orange before the stadium lights take over. It’s all picturesque. The rodeo started with a grand entry by 3-year-old Blakely Bruinsma, granddaughter of Bill and Tracy and daughter of Megan Bruinsma, their oldest. Blakely is fifth-generation Crider descendant if you’re counting. With the help of her dad, Rusty Bruinsma, and the protection of what looked like a cowboy hat-shaped helmet, Blakely and her pony, Emmy, made a second appearance during the barrel racing slot. To keep the tiny horse calm, the announcer instructed the crowd to withhold any claps and cheers, and for the most part, you could hear a pin drop. Other rodeo events included bull riding, team roping, mutton busting, and even a calf scramble where hundreds of kids swarmed like ants after red ribbons attached to calves’ tails. As far as family-friendly entertainment, there are few better ways to spend a Saturday night in Texas.

By the time the Crider’s the rodeo winds down, Crider’s the dance hall wakes up. The large cement floor is surrounded by a ring of picnic tables (which you can reserve for $20 online). At 10 p.m., there were still small kids bouncing around.

Bill Moore remembers being one of those kids. His parents, busy with running the thing, would put him to sleep under the picnic tables. When Tracy first started helping with the dances, she remembers walking through the parking lot and seeing windows down and sleeping kids in the back of every seat. “When he was a baby,” she says pointing at her son Dakota, now a dad himself, “was after the building burnt and we just had an old makeshift concession stand kind of thing… And it had the backseat of grandma’s old suburban just for somewhere to sit, and that’s what he used to sleep on when he got tired.

“And then whenever we built this,” Dakota motioned to the bar and kitchen scape around us, “I’d fall asleep on chest freezers and they had to move me every time that had to get something.” Eventually, Grandma Crider bought a cot for the young Criders to doze on so the big Criders could keep the dance hall tradition alive. On the night I visited, dancers of every generation swirled around, old-timers and teenie boppers, alike.

To get to Crider’s, go past Kerrville, through Ingram, and follow the Guadalupe until it swells with a bit of cypress magic. This cool little pocket of riverfront Hill Country seems to beg for a summer romance, and just about everyone I spoke to seemed to have a story or two, including Tracy.

“A few years ago a couple came, they were celebrating their 60th wedding anniversary, and their kids asked them, ‘Well, where do you want to go?’ And they said, ‘We want to go to Crider’s.’ Why? They met here.

“They met when it was across the road… and there was an old store and they had a pavilion they danced under, and they had met Friday night, which was just kind of like a sub dance. They used to have music Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday…. And so she had told the guy, the boy that she had met [on Friday], ‘Yeah, I’ll come with you tomorrow night’, because he asked her to come back the next night. Well, during the daytime [on Saturday], this other boy that she was sweet on called her and asked her to the dance, and she said yes.” As fate would have it, her mother overheard the phone call, knew her daughter had double-booked herself, and immediately made her cancel the date with the second boy. “And so she ended up going with the original boy that asked her, because her mother made her, and they ended up getting married.”

On the Crider’s social media page, so many comments were like Yolanda Ramirez’s: “Have come here since I was old enough [to] put boots on and dance. Great family memories.” But of all the 5-star reviews, Sara Kendrick’s summed it up: “Fell in love with my hubby while dancing in the middle of the Criders dance floor. Criders on a Saturday night is a rite of passage.” Sara, who is from Dallas, spent summers from age 8 to 18 at Camp Sierra Vista, first as a camper, then a counselor. Her dad camped and counseled at the summer camp, also. When Sara was 16, she met Sean, an 18-year-old Kerrville native. They taught horseback together. “Sean was never a camper,” Sara told me, but a Camp Vista rep had convinced him the summer job would be better than “stretching wire on a ranch,” with cuter coworkers, to boot.

Sara remarked about Crider’s role in it all. “We would have every third night off. And if it fell on a Saturday, you were just in luck.” It was on one such Saturday that, surrounded by her best friends, Sara went to Crider’s as Sean’s date. She remembers being young, and nearly in love, and time slowing down for a bit on the dance floor. “It was like this blur of people dancing all around,” and there they were, two-stepping in the middle, forgoing the outside current of dancers. “We were in the middle” she paused, seeming to look for the explanation of why they were in the middle of the dance floor, “because he thinks he owns the place wherever he goes,” she smiled. The two got married and moved around for about ten years where Sean worked on ranches like The King Ranch before settling down in Hunt, moments from where it all began. For Sara, Sean, and their kids, Crider’s isn’t only a rite of passage, but just a regular Hunt night out. “Oh yeah, my kids have grown up going there…on Friday nights, it’s more locals, [and] they do a catfish dinner… kids are just riding around on bikes and scooters all over the dance floor.”

Sara told me she had heard, that her husband had heard, that Bruce and Charlie Robinson’s parents had also met at Crider’s. I confirmed this, and it just figures that such a pure Texas sound was born from this sweep of Guadulape riverfront.

As evening hit, the Moores disappeared into the seams, happy family clusters filling out the middle. I saw Dakota, once, who gave me a kind and hurried pat on the back as he weaved his way through a crowd waiting for a beer. The kitchen got slammed, and Tracy, I’m told, was helping get food out.