In the dimly lit listening room at Gold Rush Vinyl in Austin, the sound of music hums from a vintage Victrola record player. Dressed in jeans, sneakers, and an Aerosmith T-shirt, founder Caren Kelleher paces the room, looking right at home amidst the relaxed furnishings and cozy cubbies packed with collected vinyl.

Before founding her record production company in 2018, Kelleher grew up in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. Music played a big role in her childhood, and there was always something on the radio, from Broadway musicals, to Rock and roll crooners like AC/DC and David Bowie.

“In middle school and high school, I was kind of known for how much I loved music,” she said. “I had a teacher who knew I loved The Beatles, and he used to let me come in at lunchtime and go through his record collection.”

Later, she studied business at Emory University in Atlanta and pursued her passion for music through internships at MTV and Paste Magazine. “It was amazing to work for a startup in music, to see all sides of the industry, and to get to be a part of making artists more successful,” Kelleher shared of her time at Paste.

After graduating from Harvard Business School, she took a job with Google where she headed up music partnerships. “I got to learn from such amazing leaders, especially female music industry professionals,” she said. On the side, the budding entrepreneur was also managing a handful of indie bands when she began to notice how important vinyl was, particularly for independent artists. As companies like Napster and Spotify came onto the scene, the decline of physical sales revenue meant more and more artists were offsetting their losses through concerts. In the process, selling merchandise like vinyl became critical, particularly on tours.

In the digital music era, artists today earn a dismal $0.0083 in royalties for every stream, meaning the average American band can only make minimum wage by hitting 2,500,000 YouTube views or 368,000 Spotify streams. Alternately, they can sell one hundred vinyl records and make the same amount. “To see that really pointed out to me that vinyl was going to become more of an important merchandise tool for musicians,” she explained.

At the same time, Kelleher also knew how difficult it was to get vinyl made. After record sales went into decline in the mid 1980s, and into the 1990s and 2000s, a lot of the traditional pressing plants closed. When vinyl started to rise again in recent years, the plants that did exist were backed up with work, and independent artists, or those who didn’t have major record labels, were impacted the hardest. “The indie artists that really needed the vinyl to live on in terms of revenue were the ones cast to the side,” she said.

Knowing this, Kelleher began to brainstorm a business that made high-quality vinyl at faster speeds, ultimately helping independent musicians earn more money from their music. In the past fifteen years, vinyl sales have seen consecutive double-digit growth, and in 2021 alone, there was a 47% spike. The reasoning behind this surge is multi-faceted, though one factor is certainly the mounting interest from Gen Z and others discovering the format.

“There is a Professor at Harvard Business School named Ryan Raffaele who has done a lot of research on why certain technologies come out of retirement,” explained Kelleher. “One of the things he pointed out is that vinyl, having it on your shelf, letting people see what music you like, says not only something about you to the people entering your space, but reminds you on a daily basis of who you are and what your personality is. I think vinyl gives us that in a way that digital playlists don’t.”

A few years ago, Kelleher had an intern who said that the reason she collected vinyl was because for her whole life, her music collection had been hidden in her pocket where no one could see it. However, when people came into her dorm room and saw a St. Vincent record on the wall, they knew exactly the kind of person she was. In this way, collecting vinyl and displaying it at home can be a form of storytelling and self-expression.

After drawing up her business plan and securing initial funding, Kelleher began looking for the right place to land. “The city of Austin really wanted this business here,” she said of her decision to leave California. “The governor rolled out the red carpet to make it clear that if I moved my business to Texas they would support me. I picked up my whole life and moved here to do this.”

Today, Gold Rush Vinyl is making waves in the industry as a dynamic, woman-owned American manufacturing company. Apart from being one of only two fully-woman-owned vinyl pressing plants in the world, more than 50% of Kelleher’s full-time employees are women, and 89% of their TikTok followers identify as women as well. “We have built this really cool community of vinyl-loving women,” she shared.

Since its founding, 100% of the brand’s sales have been inbound. From local artists to national names like Dolly Parton, Weezer, and Tenacious D, along with occasional podcast and soundtrack jobs for movies and video games, the company has worked with wide-ranging talent – much to the founder’s delight and surprise. “I thought coming to Austin, it would be a lot of singer-songwriters, a lot of Willie Nelson-esque music, and I have been really taken aback by the creativity and different genres we get.” Thus far, she and her team have pressed around 1,500 different record titles, not to mention hundreds of thousands of records, with artists ranging from Reckless Kelly to Kristin Chenoweth and Grammy winner, Rüfüs Du Sol.

Much like the name of her company, Kelleher’s entrepreneurial vision is fueled by a pioneering spirit. At the start of her Gold Rush journey, the founder chose to incorporate new manufacturing techniques and more efficient processes at her pressing plant. “We looked at every part of our system and thought about how can we better use our water? How can we better use our electricity? How do we keep our waste rates low so that we are not sending bad product out or putting more into circulation and trash,” she said. “I was shocked when I started working in this industry at the waste, and how acceptable that standard was,” she said. “I spoke with other press operators, and I would be told seven out of ten is the best you are going to get. Perhaps because I hadn’t done this before, I challenged my team to do better.”

When it came time to build her 8,400-square-foot manufacturing facility, she hired a group of people outside the vinyl industry to help. “Our contractors had worked on big Pepsi processing plants and dairy farms and things like that that use very similar infrastructure,” she said. “We borrowed best practices in engineering from them, rather than following the blueprint that every other pressing plant was using. As an outsider, what I saw was the blueprint isn’t working, so what can we do instead to create our own system?”

She also contacted various people who had built boiler and steam systems in other industries, asking for tips and insights on expansion planning. A stroll through her pressing plant today reveals the network of chillers and holding tanks, steam generators and water filtration systems, softeners and pumps that make the pressing process possible. “It’s very scientific,” she said of the facility. “I benefitted from being naïve and not knowing quite how much I was getting myself into.”

Today, the entrepreneur credits her time in Silicon Valley for teaching her how to use technology in an effective way. The machinery used at Gold Rush Vinyl incorporates custom-built software to streamline processes, and every record they make is pressed in-house.

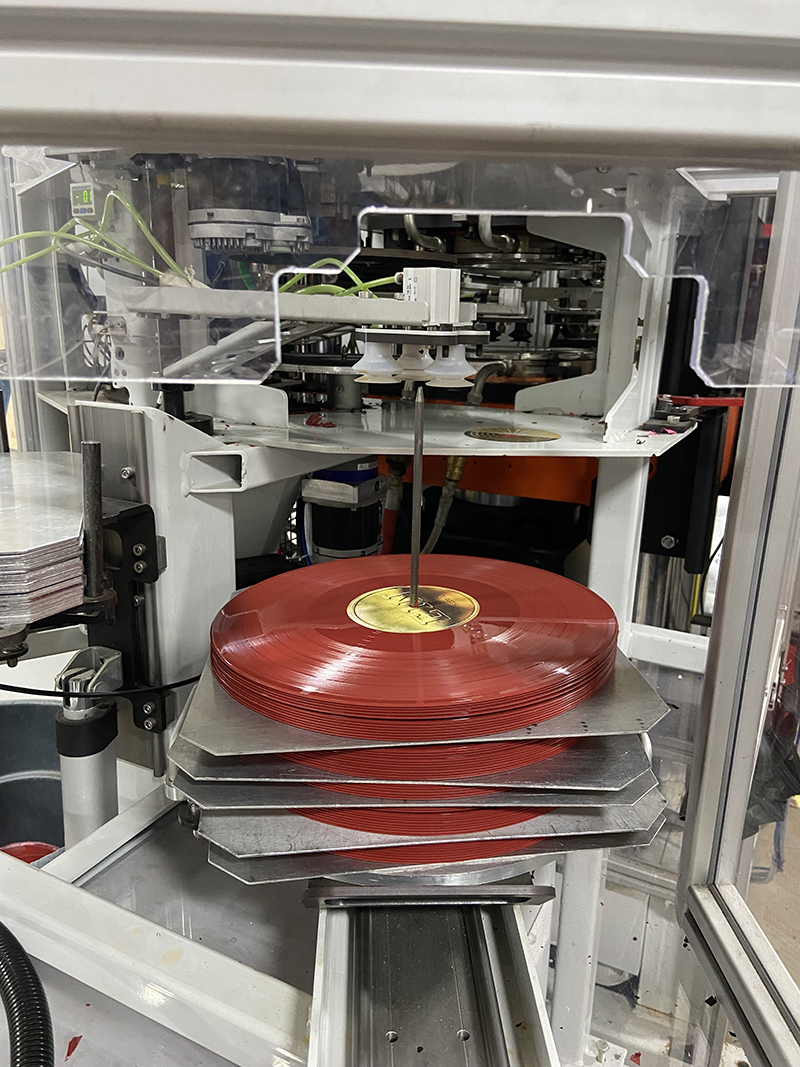

Currently, the pressing takes place on two automated machines, a stark contrast to the manual machinery from the 1960s and 1970s. The process begins with small pellets of PVC plastic being poured in and melted in an extruder barrel. This plastic is formed into a puck or biscuit that is ultimately pressed into a vinyl record. Kelleher partners with a company in Nashville to make their thin nickel stampers, which are negative impressions of a master disc. After those are clamped into the machine, the pressing commences through high heat and pressure, before the record is cooled and trimmed. The entire process lasts from thirty to thirty-five seconds. Walking through the plant, the machines hum with a cathartic cadence. “There is something really rhythmic about them,” said Kelleher. “When they start, it almost sounds like ocean waves.”

Every record that comes off the line, be it a 7-inch or 12-inch vinyl product, is then hand-inspected to ensure there is no marring, stitching, or flaws. “We track data pretty intensely to understand for any given material, day, or temperature what the waste rate is,” she said. Of the hundreds of thousands of records that have left their factory to date, less than 00.5% have been returned for quality concerns. The waste that does accumulate is upcycled and crafted into things like vinyl flower bouquets, a popular item on their website, or sold to companies who then turn them into sunglasses or iPhone cases, for example.

Before the pandemic, the team at Gold Rush Vinyl averaged six-week turnaround times on projects, a rate that is three times faster than the industry average. By June 2020, that number jumped to fifteen weeks. Now, their turn times are impacted by things such as a lack of raw materials, including particular colors of raw vinyl that are globally out of stock.

“One of the really concerning things about the vinyl industry is how thin the supply chain is. For any part of the process, there are usually only two to three companies that make the goods we need,” she shared. “So particularly during the pandemic, and now with the supply chain debacles America is facing, it has been really critical to be a good partner to our vendors to make sure we have the raw materials needed to actually produce the records.” Currently, their record jackets are supplied through various printers across North America, and the nickel stampers are made through a partner in Nashville. Meanwhile, the PVC plastic comes from Asia, where plastic prices are up globally 269% in a single year. Still, there is hope that things will improve in the months ahead.

Looking forward, Kelleher is excited about the future of her business and the industry at large. “Plants are opening in Tennessee in the next two years and the European plants are also doubling down, so we are really excited to focus on quick turnaround projects and independent artists and let the big plants take the Justin Bieber, Ed Sheeran, Adele kind of work that is really tying up the vinyl industry right now.”

She is also adding two new machines, which will double their annual output, in addition to a machine that will make 24-karat gold-plated records for fans. “I’m especially interested in collectors and why they collect vinyl, so our 24-karat gold record business – which will be called Gold Records USA – will allow people to own a piece of music history.”

With all her growth thus far, Kelleher is quick to credit her lean yet mighty team, who helped Gold Rush Vinyl weather the pandemic and come out stronger than before. “We are at a point where we’re backed up almost a year, and the orders just keep coming,” she said. “It is a really special problem to have, a ‘platinum problem,’ as they say.”

Outside of work, Kelleher enjoys mentoring young women and the next generation of aspiring entrepreneurs. Recently, she has been guest lecturing everywhere from The University of Texas to Austin Community College, Texas A&M, and her alma mater, where she spent a whole semester working with marketing students on a case study about her company.

Whenever she can, she enjoys heading to the Hill Country where she’s pressed vinyl for a community of talented artists such as Israel Nash of Dripping Springs. “I started going out more during the pandemic to meet other business owners, particularly vineyard owners, who faced similar pandemic challenges,” she said. “When I was out there, I would often see musicians performing live, collecting tips, and selling merchandise, which gave me encouragement. It reminded me of the real impact our work had, if we could just keep making records for performing artists.” The Hill Country’s array of intimate, outdoor venues were also increasingly popular during the pandemic, with a wave of music lovers visiting from across the state.

Looking back on her journey, Kelleher can trace her entrepreneurial origins to her youth on the east coast. “I’ve always benefitted from having a family that would hear my crazy ideas and never told me it was impossible,” she said. Glimmers of that early encouragement and support continue to fuel her. “Every day when I left home for school my Mom would say ‘Be brilliant today’ – she wanted me to shine.”

Visit Gold Rush Vinyl online at

goldrushvinyl.com and follow along on

Instagram and TikTok @goldrushvinyl