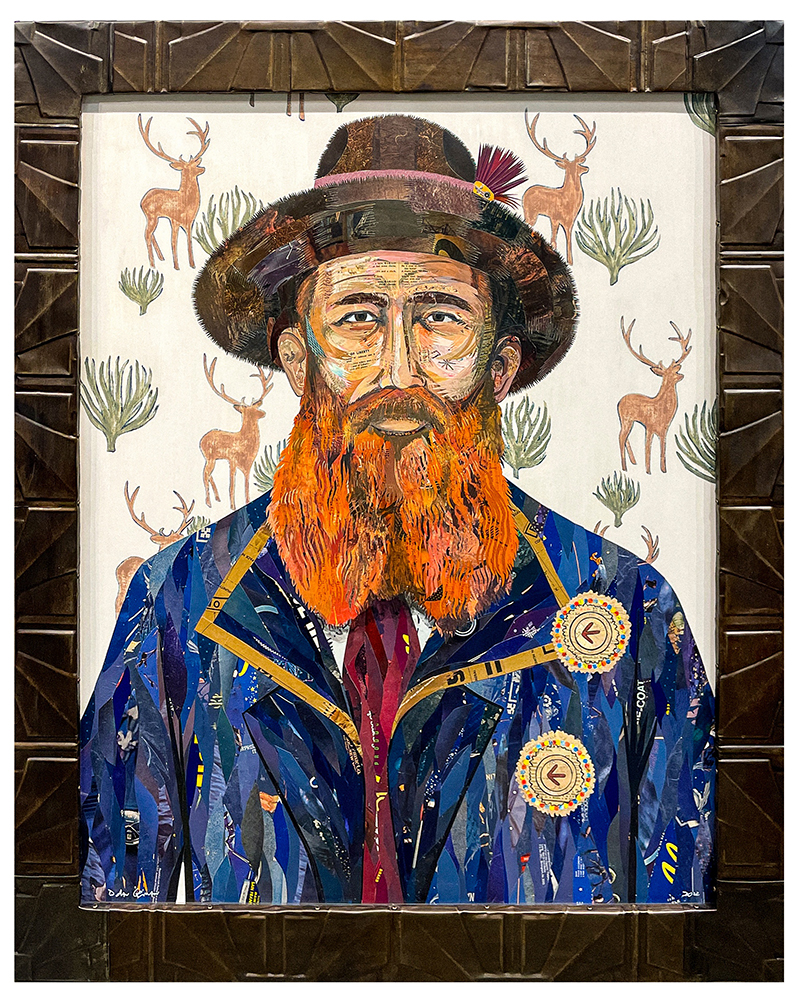

Native Americans had never seen a man like John O. Meusebach. He was a giant (he stood 6-feet, 2-inches) with blue eyes, red hair and a red beard that flapped in the breeze like Spanish Moss. The Comanche called him El Sol Colorado – “The Red Sun.” In an awkward moment, women from the Waco tribe pushed him into the Comal River and tried to wash the war paint out of his hair.

His unusual appearance attracted attention, but beneath that colorful exterior was a formidable personality. The fate of the early German settlements in Texas hinged on Meusebach’s leadership and his remarkable relationship with the Comanche.

The story of his early life seems inconsistent with his role in taming the wild Texas frontier. John O. Meusebach was born Otfried Hans Freiherr von Meusebach in 1812 in the German Duchy of Nassau. (Germany was not yet a unified country but a cluster of feudal kingdoms and principalities ruled by noble families.) He was, as his fancy name suggests, a child of nobility, but his childhood was not typical of the conservative German upper class.

Meusebach’s father was a judge with an interesting circle of friends. He knew the military theorist Karl von Clausewitz, and he was cordial with Goethe, perhaps the most influential writer in the German language. At different times the younger Meusebach came home to find the scientist Alexander Humboldt, the poet Hoffmann von Fallersleben, and even the Brothers Grimm sitting in his father’s living room. Those visitors were progressive thinkers, and from them Meusebach absorbed ideas about freedom, liberty, democracy, racial equality, and separation of church and state.

Although Meusebach’s talents would pull him in many directions, his first love was the natural world. (A description of Enchanted Rock sparked his early interest in Texas.) He attended the mining and forestry academy at Clausthal. Later he studied law and finance at the University of Bonn. He had a short but impressive career in law and city management before taking up his post as an agent for the Adelsverein, a group of German noblemen who hoped to plant a German colony in Texas.

In 1844, the Adelsverein, acting as the Society for the Protection German Immigrants in Texas, purchased colonization rights, sight unseen, to the Fisher-Miller Land Grant, an area of frontier Texas between the Llano and the Colorado Rivers. The first German settlers began arriving in Carlshafen (Indianola) on the Texas coast later that year.

Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels was the first Commissioner General of the Adelsverein in Texas. He founded New Braunfels on the Comal River as a base of operations and a depot between the port of Carlshafen and the promised land in the Fisher-Miller Grant.

Meusebach succeeded Prince Carl in 1845. Only 33 years old, Meusebach had already earned a reputation as a talented organizer and administrator. A contemporary described him as “a substantial man, the best educated and most practical of all the Verein members.”

Prince Carl and Meusebach represented the contrasting political philosophies of mid-19th century Germany. The prince, an officer in the Austrian army, was aristocratic and feudalistic. Many Texans, even the German immigrants, found him a comical figure in his skin-tight military uniform and his fancy hat with rooster feathers. Meusebach, on the other hand, was unpretentious, democratic and all business.

Unlike Prince Carl, who came to America to establish a German state, Meusebach left Germany to take part in the American democratic experiment. That difference was an important distinction. Soon after arriving in Texas, Meusebach gave up his string of German titles and became a naturalized citizen of the United States. For the rest of his life he was simply John O. Meusebach.

Even among the German settlers there was little desire to be a part of Germany. They had left that world behind. When Prince Carl, at a ceremony in New Braunfels, ordered the guard to fire cannon shots and raise the Austrian flag, the settlers, in protest, assembled in the market place and raised the Texas flag. For them Germany was the past. Texas was the future.

Meusebach arrived at his post in New Braunfels thinking the immigration project was in good order only to discover crippling financial and logistical problems. Prince Carl was a terrible bookkeeper. The Adelsverein owed thousands of dollars (the exact amount took months to determine) and was racking up more debt by the day. The entire project was underfunded. There wasn’t enough money to feed and house the unhappy German immigrants already in New Braunfels and at Carlshafen on the coast. Hundreds more were in route from Germany.

Meusebach faced a monstrous job. He had to reconcile the financial accounts, hold creditors at bay, feed and house hundreds of immigrants with inadequate funds, transport new arrivals from Carlshafen to New Braunfels and keep impatient settlers from revolting. He held the colony together, but it took all of his skills to do it.

Another serious problem was the possible loss of Adelsverein property in the Fisher-Miller Grant. The promise of that land brought German immigrants to Texas in the first place. The Fisher-Miller Grant followed a timeline, and the clock was ticking. If the Germans hoped to reach their promised land, the property had to be surveyed and then settled.

On an inspection trip out west, Meusebach chose the site for a way station in the high Hill Country between New Braunfels and the Fisher-Miller lands. The location was a naturally beautiful valley, encircled by seven hills, with two flowing creeks. Meusebach called it Fredericksburg after Prince Friedrich of Prussia.

Thirty miles north of Fredericksburg, the Llano River formed the southern boundary of the Fisher-Miller Grant. That part of Texas, known as San Saba, was the hunting ground of the Comanche, and there were many legends about it. Europeans feared going there after the Comanche attacked and destroyed the mission near present-day Menard in 1758. Jim Bowie, who didn’t scare easily, went there in 1831 looking for the lost (and still missing) Spanish silver mine. The San Saba country had a dark, mysterious and dangerous reputation that added to Meusebach’s troubles. Surveyors refused to go near the place.

Meusebach asked the state of Texas for help in negotiating with the Comanche but got no encouragement or assistance. So out of desperation he sought out the natives on his own to make a treaty. (His model was William Penn’s agreement with the Delaware.) Meusebach’s move was risky (some said suicidal), but he had to try. Peace and the promised land hung in the balance.

The Germans rode out of Fredericksburg in late January 1847. The caravan, including three wagons and about 40 men, crossed the Llano River on the first of February.

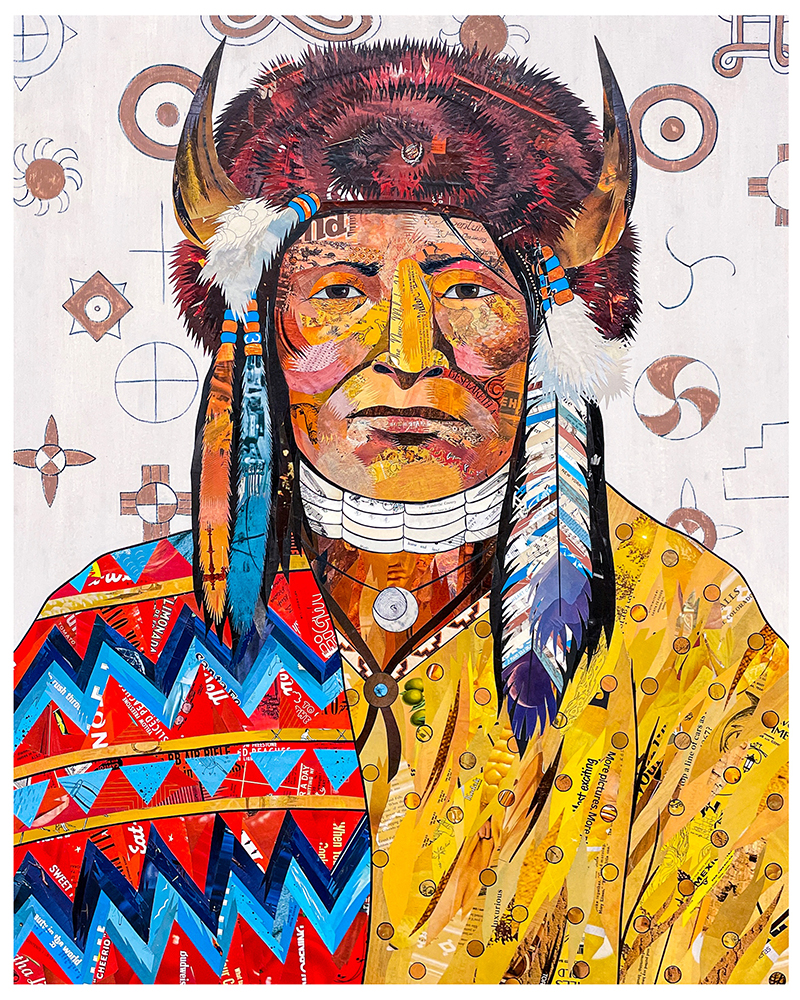

Contact came on February 5 when Chief Ketemoczy (who had been watching from the hills), with a small party of Comanche warriors, rode out to confront the Germans near the present-day town of Mason. When Ketemoczy asked interpreter Lorenzo de Rozas the name of his chief, Meusebach, sitting tall in the saddle, his red hair gleaming in the sunshine, armed only with an iron will, rode forward, introduced himself and convinced Ketemoczy of his friendly intentions.

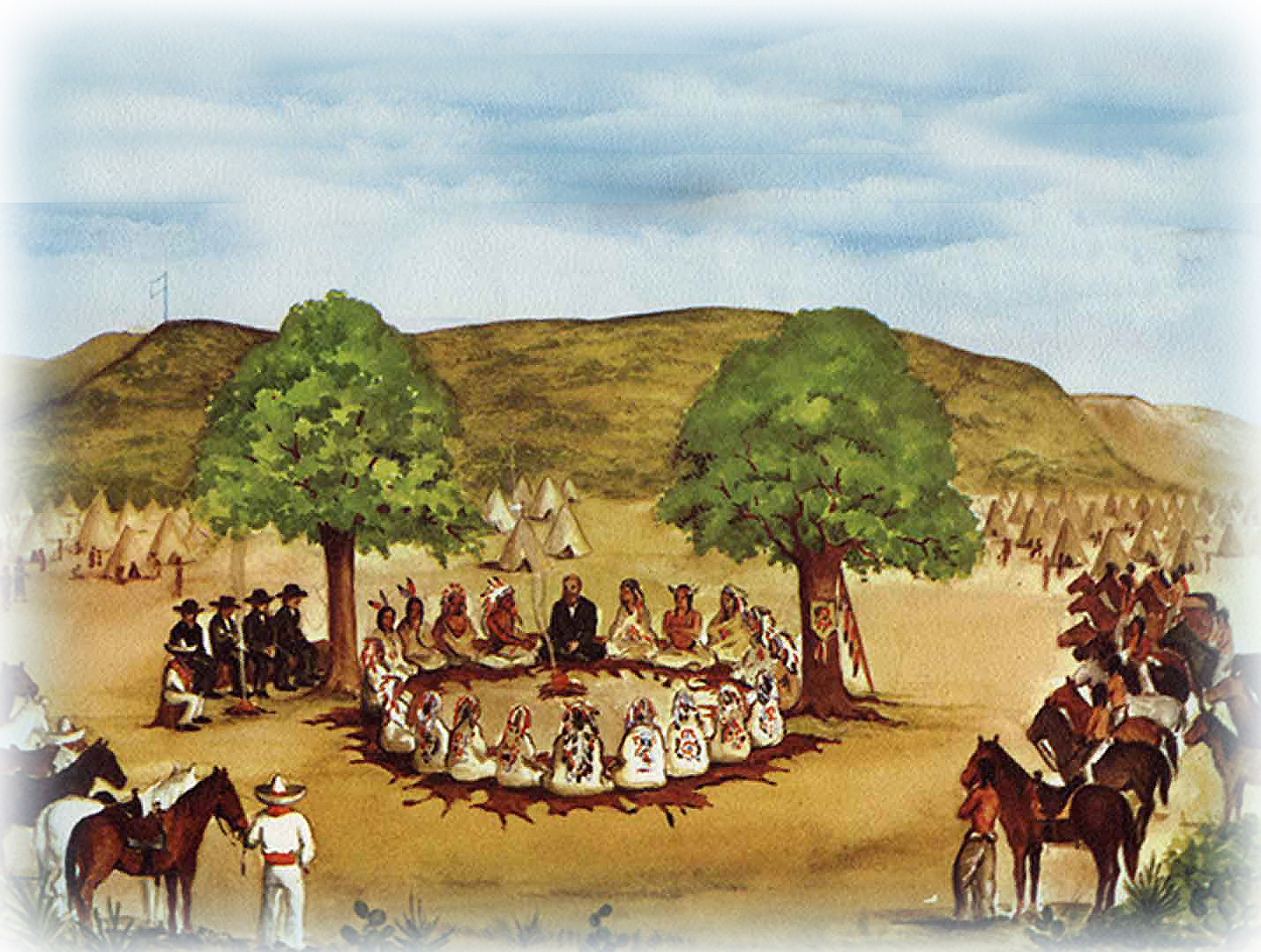

Ketemoczy arranged for Meusebach to meet Chief Santana. Then in early March, at the Comanche camp on the San Saba River, Meusebach negotiated the landmark peace treaty with Santana, Buffalo Hump, Old Owl and the other Comanche chiefs.

Meusebach’s leadership and his treaty helped the German colonies in Texas grow and flourish, but settlement in the Fisher-Miller Grant did not go as planned. Only a few Germans took advantage of the free land north of the Llano River. They had made a home in New Braunfels and Fredericksburg, and they had no desire to go on. They had already found the promised land.

For more of the story read John O. Meusebach: German Colonizer in Texas, by Irene Marschall King.