Comfort is not your typical Texas Hill Country town. Its residents enjoy a more leisurely atmosphere and a slower pace than their more hurried neighbors in Fredericksburg, Boerne and Kerrville. Not that Comfort has a problem with its easy-going reputation. Citizens wouldn’t have it any other way.

A 1929 Diamond Jubilee souvenir book about Comfort states, “a more appropriate name could not be found to apply to this place; so befitting its location and surroundings, its peaceful and contented inhabitants, its orderly and inviting construction of homes and its spotless yards and streets.”

Not much has changed in the last century.

The community began in the early 1850s when a group of Germans from New Braunfels put down roots in the Hill Country backwoods, 50 miles northwest of San Antonio. Unlike some early Texans who embraced the solitude of the wilderness, the sociable Germans preferred the close company of other Germans. To draw settlers to the area, Ernst Hermann Altgelt laid out 300 town lots at the confluence of Cypress Creek and the Guadalupe River.

The settlement grew and over time developed a distinctive libertarian flavor that can be traced to the Freethinkers. This group of educated German liberals, intellectuals and political activists came to Texas in the mid-19th century. They settled in Latin communities like Bettina and Sisterdale but many Freethinkers eventually migrated to Comfort. By the 1860s, half the Freethinker population of Texas lived in the little German village on Cypress Creek.

Apart from the literal meaning, Freethinkers tended to be suspicious of government and resistant to the authority of the church. They opposed slavery, and that opposition put them at odds with most other Texans. Freethinkers took freedom seriously.

Those strong feelings about liberty, equality and freedom (of thought and speech as well as action) had a profound and lasting impact on the area. Comfort, with its ornery streak of independence, had no formal government or police force. Citizens organized the village along cooperative lines.

Comfort had no church until 1892. Few homes had Bibles. Mourners sang sentimental German ballads at secular funerals. Glen Lich wrote in his book The German Texans, “When occasionally a minister conducted a funeral and asked for the Lord’s Prayer, they . . . did not know it.”

A 1903 newspaper article noted that Comfort had “no mayor, no lawyer and no preacher. They are looked upon as a needless expense.

“These people do not regard Sunday above any other day,” the article continued. “Yet they are law-abiding. The secret of their success is in their thrift.”

Not only thrift, but resilience and wit helped the Germans thrive. In fact Comfort got its name from a streak of twisted frontier humor.

The Freethinkers, university educated and not accustomed to manual labor, did not enjoy the sweat and hard work necessary for survival on the wild Texas frontier. They called their home Camp Comfort, hoping life would get easier. When they got no relief, they shortened the name to Comfort because there wasn’t any.

That same sense of humor saw the Comfort Germans through mishaps and snafus. At an early July 4 celebration, kegs of beer from a San Antonio brewery arrived in Comfort a day early. Beer went flat in a hurry in those days before refrigeration, so fast-thinking organizers fired the cannon used to call residents in case of Indian attack. The responders’ anger at the false alarm washed away with a few beers. That year Comfort celebrated July 4 a day early.

But the best of German humor came at the expense of the listener. In the early 20th century, a group of Comfort men played cards in an abandoned building on 7th Street. Their wives jokingly called the building Bolshevik Hall. The harmless old guys probably did talk a little treason but were hardly Bolsheviks. Still, the name alarmed visitors who believed the communists had a foothold in the Texas Hill Country, but locals got the joke.

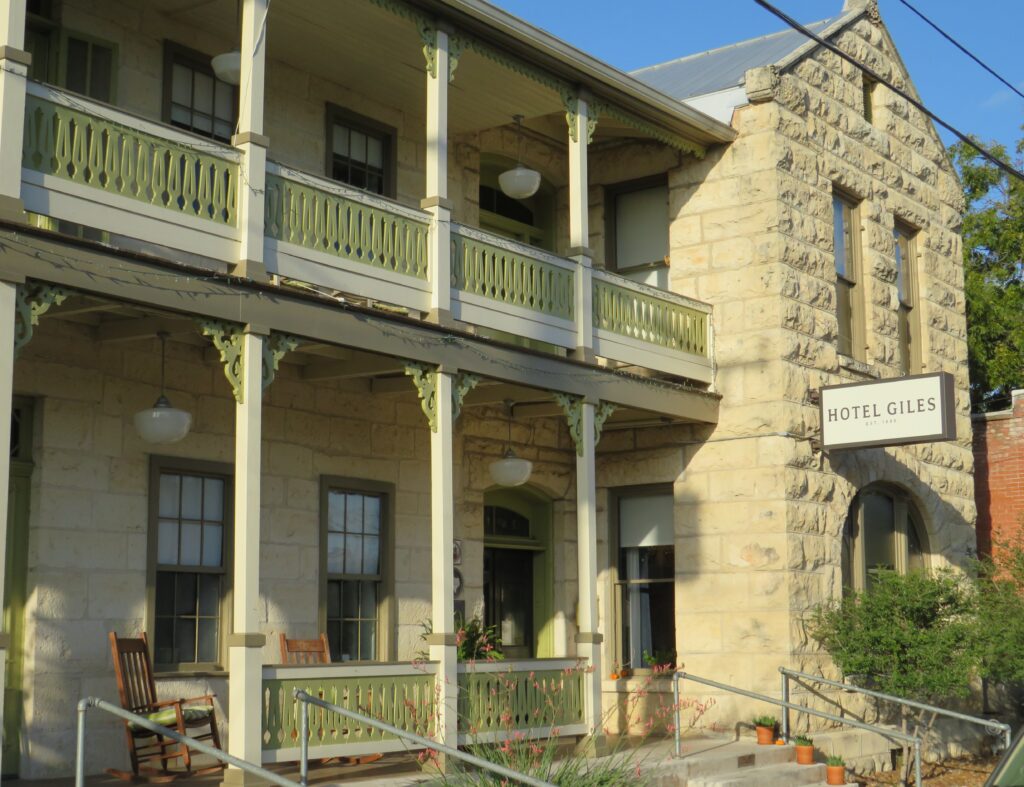

When the railroad came through in the 1880s, visitors from the city streamed into Comfort to spend the “heated season” at the Ingenhuett Hotel at 717 High Street. Peter Ingenhuett and Marie Karger commissioned famed English architect Alfred Giles to design and oversee the building of the cut limestone hotel (today the Hotel Giles) in 1880.

Giles, who lived on a ranch northeast of Comfort, left his mark etched in stone all over town. In addition to the hotel, he designed the August Faltin Building at Main and 7th Streets, the Ingenhuett Store at 830 High Street, the Ingenhuett-Karger Saloon at 727 High Street, the Paul Ingenhuett House at 421 8th Street and the Old Post Office building at 184 High Street.

The heart of Comfort, along Main and High Streets, saw hard times in the mid-20th century, but today that part of town has come back more glorious than ever. Except for the Ingenhuett Store (destroyed by fire in 2006) all the other Alfred Giles-designed buildings still stand in what is one of the best preserved and most beautiful19th-century business districts in Texas.

Two of the leaders of that preservation effort, Dr. Bob Potter and his wife Diane, found Comfort in the 1980s, purchased the old rundown hotel and nursed it back to life. Today their house, on a shady Comfort street, is a Norman Rockwell image from small town America. The Saturday morning view from an easy chair on the front porch is like a scene from a 1950s television show.

“I came to Comfort for the architecture, the people and the quiet atmosphere,” Dr. Potter says, waving to a neighbor strolling down the sidewalk in front of his house. “It’s so peaceful here. It’s off the main road. It’s not as busy as most other towns in the area.

“Comfort isn’t paradise,” he adds, “but it’s close. My friends are here. Everything I need is here. I wouldn’t live anywhere else.”

Today, as always, Comfort stubbornly goes its own way. It remains unincorporated and small by design. It is less interested in growth but more interested in protecting its rural values and in keeping its historical integrity intact.