Llano, famous for cowboys and barbecue, once seemed destined to become the Pittsburgh of the West after the discovery of iron ore turned this frontier village into a boomtown. The Badu Building, two blocks north of the river on Bessamer Avenue, is an historic treasure from those wild and crazy days before the great Llano iron boom went bust.

Like the biblical church built upon the rock, the town of Llano is firmly planted atop the glittering granite domes of the Llano Uplift – some of the most unique and ruggedly handsome countryside in the world. Just about every mineral known to man can be found in the hills around Llano but not always in paying quantities.

Since the days of the Spanish explorers, the Llano country has had its share of gold and silver strikes, but none of them panned out. Precious metals have a way of teasing miners while playing hard to get.

Then in the 1880s prospectors discovered Iron Mountain, northwest of Llano near Valley Spring. That discovery, like so many others, looked promising. In 1887, the Wakefield Iron and Coal Company bought several tracts of land at Iron Mountain. Outside investors got excited. Property values climbed. Well-dressed strangers appeared in town talking fast and spreading money around.

“Llano in the 1880s was a village on the south side of the river,” says JoAnn McDougall at the Llano County Historical Museum. “There wasn’t much on the north side. The river was a barrier. But that all changed after the discovery of Iron Mountain. A bridge was built in 1892. Then the railroad arrived. Several stores and hotels went up near the depot on the north side. Llano started to grow.”

The future looked brighter than a blast furnace. The town laid out new streets on the largely undeveloped north side of the river and gave those streets names with a purpose like Birmingham Avenue, Pittsburgh Avenue and Sheffield Avenue. Llano prepared to take its place among the great iron and steel towns of the world.

Newspapers spread the word about Llano, recklessly playing up the magnitude of the region’s mineral resources. “Llano iron ore is the finest on the continent,” one story claimed. “Iron Mountain will produce 2,000,000 to 4,000,00 tons annually after the first year.”

Suddenly a tiny settlement that had trouble finding two nickels to rub together had a lot of money to spend. All that money needed a bank, and in 1890 a group of investors organized the First National Bank of Llano. Then to house the bank, the Llano Improvement and Furnace Company hired the Austin architectural firm of Larramore and Watson to design a suitable bank building at 601 Bessemer Avenue, named after Sir Henry Bessemer, the English engineer who developed the process for turning molten iron into steel.

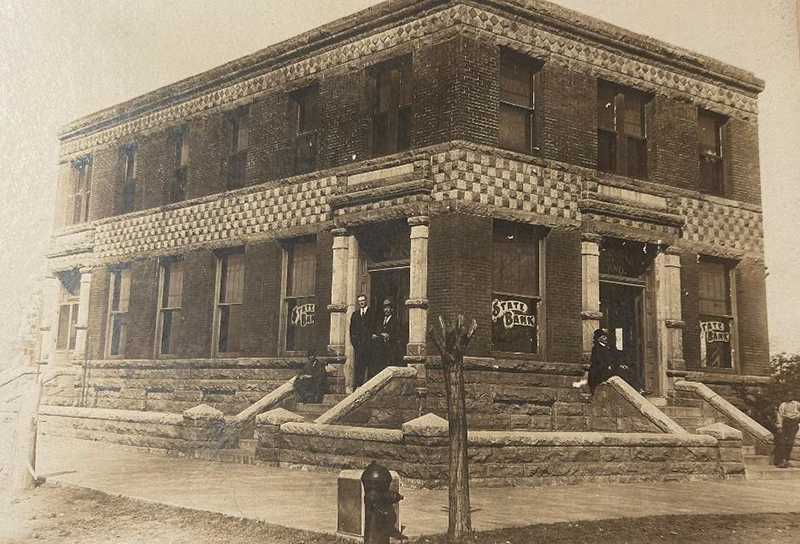

Completed in 1891, the simple, elegant two-story building is constructed of red bricks with three distinctive diagonal bands of gray granite blocks aligned in a checkerboard pattern. Wide granite steps lead up to three sets of double doors, and a short granite wall separates the structure from the street and sidewalk.

“Builders used local materials whenever possible,” JoAnn McDougall says. “The granite blocks came from a Llano County quarry. A kiln here in town fired the bricks.”

The rectangular, flat-roofed building contains elements of the Neo-Renaissance style of architecture, inspired by the classic forms of ancient Greece and Rome. The building projects importance and permanence. It draws attention.

Functional as well as attractive, the building’s lower level, with its large open space and white marble floor, housed the bank. The second level served as office space. Architects designed the building to be the financial cornerstone for business and the centerpiece for the transformation of Llano from a frontier village into a modern industrial city.

The First National Bank of Llano pointed the way to prosperity by loaning money to start new businesses, erect new buildings and buy and lease land. No one seriously questioned the security of the loans or the certainty that property values would continue to rise.

But negative economic forces had already started to drag down the local economy. Rumors began circulating that production levels at Iron Mountain may have been overestimated. Those reports reached the outside world and scared away new investors. By 1893 the overheated economy began to cool. Property values quickly leveled off and started to drop.

The First National Bank of Llano saw disaster coming but could do nothing to stop it. The bank had outstanding loans against property now worth a fraction of the loan amount.

Then business in town slowed. Borrowers defaulted on their loan payments to the bank. In 1894 the Llano Improvement and Furnace Company, owner of the bank building, went bankrupt. That same year the First National Bank of Llano closed its doors, unable to meet its financial obligations. Lenders, speculators and businessmen lost fortunes.

Production at Iron Mountain never came close to projected levels. Some ore shipped from the mountain over the years but never in amounts once predicted.

When the iron boom fizzled and the dust settled, Professor N. J. Badu, a French mineralogist, purchased the bank building at public auction in 1898. He leased the lower floor to a reorganized bank and used the second floor as a private residence. The Badu family owned the building for most of the 20th century.

Little visible evidence remains of the Llano iron boom. A 1906 tornado destroyed some of the boomtown buildings north of the river. Other structures suffered a more mysterious fate.

“A number of buildings on the north side burned,” JoAnn McDougall explains. “The owners did it to collect insurance money. They needed cash and didn’t see any other way to get it. So many buildings burned, the insurance companies stopped insuring buildings in Llano, at least for a while.”

The Badu Building is one of the last survivors of Llano’s boomtown days. Once a symbol of broken dreams and fortunes lost, today it represents perseverance, a proud past and hope for the future.