Cowboys and camels don’t mix well, which is part of the reason the Campe Verde camel experiment never received the credit it deserved. Camels, after all, have bad breath. They walk funny. Trying to cinch a western saddle to a camel’s hump is like trying to land a Cessna on Mount Everest. No Texas cowboy with an ounce of self-respect will go near a camel.

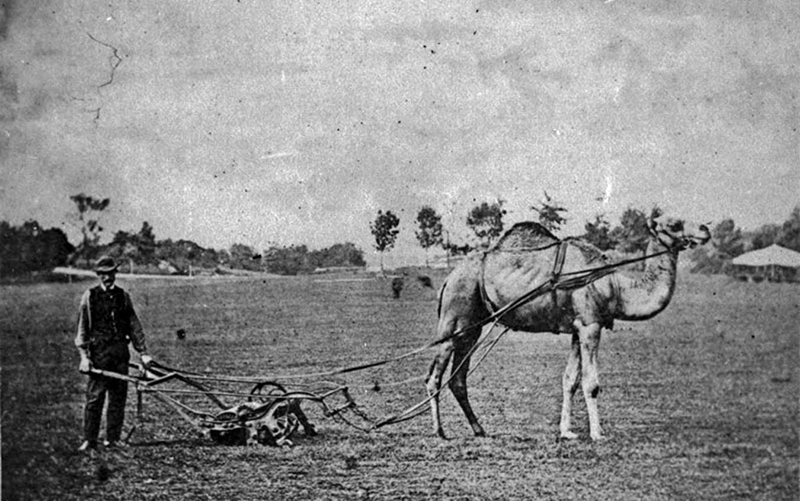

And yet using camels to haul supplies across South Texas in the mid-19th century made a lot of sense. Camels carried a heavier load than mules, and they could go days without water. They seemed a good fit for the arid South Texas terrain.

Jefferson Davis thought so. The Mississippi politician and future president of the Confederacy came to Texas as a colonel during the Mexican War in 1847. Davis took note of the dry, rugged South Texas landscape and the difficulties the army supply mule had in traversing it.

When Franklin Pierce became President of the United States in 1853, he chose Jefferson Davis as Secretary of War. By that time the army faced the problem of supplying the long chain of forts thrown up to protect settlers on the American frontier. When considering the supply problem, Secretary Davis concluded that camels would work well hauling food and equipment across the vast expanse of the American Southwest. He persuaded congress to appropriate $30,000 for a herd of camels.

The army assigned Maj. Henry Constantine Wayne as camel purchasing agent. In a ship commanded by Lt. (later Admiral) David Porter, Maj. Wayne sailed to the Mediterranean with stops in North Africa and the Middle East. He purchased 33 camels and hired a team of experienced camel drivers.

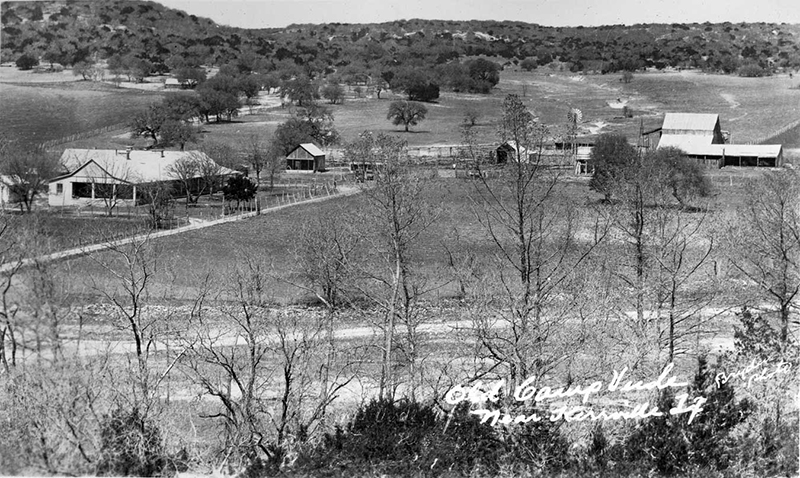

In June 1856, the drivers unloaded the camels at Indianola on the Texas coast; then drove the animals 150 miles to San Antonio in 14 days. On arrival in the Alamo City the army immediately put the camels to work toting freight the 60 miles between the quartermaster depot in San Antonio and Camp Verde in southeastern Kerr County.

Camp Verde, Texas became the headquarters of the Camel Corps. A caravansary (a fancy camel corral), built from a sketch made in Asia Minor, stood behind and downwind of the officers’ quarters.

By all indications, the Camp Verde camels served well as pack animals. Major Wayne reported that “Twelve camels carried 3,800 pounds among them and much faster than mules could have done it.” Another story told of twelve camels, each carrying 325 pounds, making the trip from San Antonio to Camp Verde in 54 hours in a continual rain that made the roads impassable for regular army vehicles.

In 1857 President James Buchanan appointed Edward Beal to survey and build a road from New Mexico across the southwest to California. Beal used two dozen camels to carry supplies. When asked how the camels performed Beal answered, “My only regret at present is that I did not double the number.”

“Camels are gentle, strong and trainable,” says Doug Baum of the modern-day Texas Camel Corps. “They are a pinch smarter than a horse. They are complacent and comfortable around people. Horses have a strong flight response, but camels are docile and even-tempered. They rarely get excited.”

When the Confederates took over Camp Verde in 1861, the compound housed eighty camels. During the Civil War, camels reportedly carried cotton from San Antonio to Brownsville, one of the few Confederate ports not closed by the Union blockade. By 1865 the Camp Verde camel herd numbered one hundred animals not counting strays occasionally spotted in Kerr, Bandera and surrounding counties.

Camels could survive in the wild because, like goats, they eat just about anything. “His (the camel’s) principal food is the prickly leaves of the cactus and the beans of the mesquite tree,” one story claimed, “but he does not confine himself altogether to a vegetable diet. When opportunity offers, he will reach up after the glass insulators of a lightning rod or a telegraph pole and conceal them in his commissary, or he will stand by the hour chewing up a wagon sheet when he cannot get the chance to eat a well rope or a wheelbarrow.”

Camels not only ate valuable equipment, they scared the daylights out of horses, which as much as any other factor sealed the camels’ fate. “The chief objection to using camels as beasts of burden in Texas,” one newspaper article noted, “is that the horses usually run away at the sight of them. This is bad for the horses and worse for the pilot of the camels if the owner of the horses should have his pistol with him.”

George Wilkins Kendall, the man who gave Kendall County its name, once watched a camel caravan sway into San Antonio. He described the wild spectacle for the New Orleans Picayune. “Just as I entered, the camels with their Arab attendants were coming in, causing a general excitement among the population, and a general stampede among all the horses within sight of the strange procession. It is not every town in the new world that can boast of having witnessed such a scene, and my own mind was carried away to Cairo and other cities of the East, where a caravan of some forty camels is nothing to stare at. The last I saw of the animals they were browsing about among the mesquite trees near San Pedro Springs, looking patient, contented, and apparently well reconciled to their new home.”

Camels performed good service in Texas but couldn’t overcome the image problem. They just looked out of place in the land of cowboys and horses.

The U.S. Army reoccupied Camp Verde after the Civil War but the quartermaster had already lost interest in camels. In 1869 the government deactivated Camp Verde and the camel experiment died with it. Carnivals and circuses bought some of the camels. Bethel Coopwood, a San Antonio lawyer and farmer, bought the last 60 camels at auction for $31 each to use as pack animals.

A few camels escaped to live in the wild. One story told of a 5-year-old boy, astonished to see a camel wander onto the parade ground at Fort Seldon, New Mexico where his father served as an officer. That boy grew up to be Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

Camp Verde, Texas passed into private hands in the 1870s. Mysterious camel sightings continued for decades.