A deserted horse barn stands like a giant mausoleum, marking the site where the Morris family built one of the largest and most sophisticated breeding and training facilities for racehorses this side of Churchill Downs. Morris Ranch, between Fredericksburg and Kerrville, bred horses for speed. It introduced lanky thoroughbreds, and a bit of Victorian England, to a world of dirt farmers, cowboys, wild mustangs and rugged Texas cowponies. Its racing silks flashed at major racetracks in the United States and England.

Long before its glory days, Morris Ranch began as a land grant issued by the Republic of Texas. In 1836 President Sam Houston presented a certificate for 35 sections (about 23,000 acres) to William Bryan as payment for Bryan’s services as a purchasing agent and informant for the Texas government during the revolution. In 1838, Bryan sold his certificate to brothers J.W. and Rufus Leavitt, prominent New York businessmen.

The Leavitt Brothers hired Jack Hayes, legendary Texas Ranger and surveyor, to carve their vast estate out of the wild public lands along the Pedernales River about 70 miles west of its junction with the Colorado. The Texas General Land Office in Austin issued a patent that transferred the property from public to private ownership.

Then in 1856 the Leavitt Brothers went bankrupt, and New York businessman Francis Morris bought the Leavitt property for about 40 cents an acre. Morris, an Englishman by birth, already owned horse training facilities in New York and Maryland. His filly “Ruthless” won the first Belmont Stakes. Morris envisioned his Texas land as an extension of his horse racing operations.

To move things along, Francis Morris granted his nephew, Charles Morris from Burr Oak, Michigan, the power of attorney to manage “the Leavitt lands on the Pedernales River.” And so began an interesting and productive administrative arrangement. One branch of the Morris family owned the ranch, and another branch managed it.

Elizabeth “Libby” Morris, Charles Morris’ sister, told the Kerrville Mountain Sun about the problems her brother faced in those final days of the open range. “A great many people had small places around the ranch and owned a lot of stock which they salted on the ranch pastures to keep them there. Mr. Morris started fencing the entire ranch and told the ranchers he would buy their cattle if they wished. They had looked upon the ranch as free grazing so long that this made them mad, and they began giving trouble by cutting fences and grazing their cattle anyway.

“Mr. Morris soon stopped this by posting large rewards for anyone caught cutting fences. In an early day in Texas stealing cattle and cutting fences were serious offenses, and these fence cutters were afraid of getting caught and soon quite making trouble.”

Francis Morris never saw his Texas lands. He died in 1886, and his son John bought the property from his father’s executors. John Morris, “The Lottery King,” spent his life around thoroughbreds and racetracks. He held a majority interest in the Louisiana State Lottery. John’s money built the thoroughbred breeding and training program that would make Morris Ranch famous.

Meanwhile, Charles Morris brought his brothers and sisters from Michigan to help run the ranch. Each sibling had a specific role. Libby ran the hotel and boarding house. Ellen served as postmistress. Clayton and Fred took charge of mares and foals. Gilbert handled the training facilities. George managed the weanlings, jacks and cattle. Albert took care of the colts, and he spent part of each year in England overseeing the Morris stable across the pond.

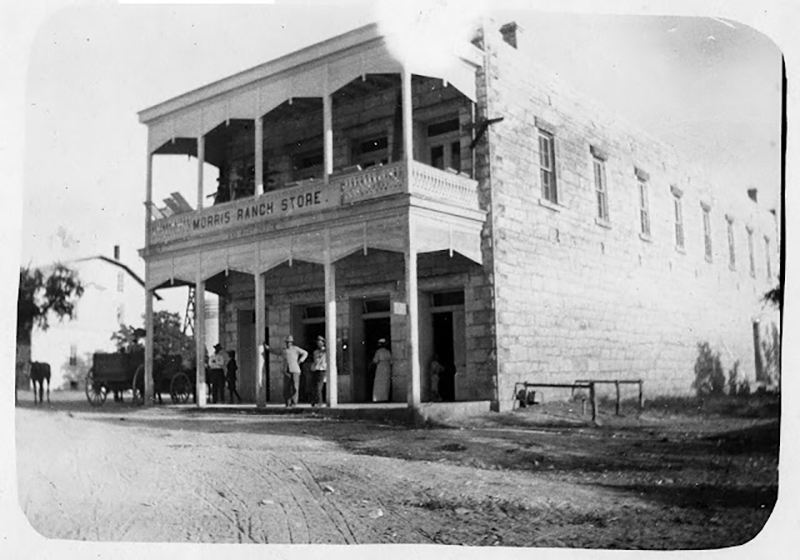

By 1895 Morris Ranch had grown into a thriving community and training ground with a one-mile racetrack, a training headquarters, a general store and post office, a drug store, a hotel and boarding house, a roller mill, a cotton gin, a blacksmith shop, homes for the men and women who managed the ranch and a jockey house with living space for 20 apprentice jockeys. About 200 people, adults and children, lived on the ranch in the 1890s not counting horse buyers from all over American and Europe who spent weeks at a time there.

When the need arose, the Morris family hired Alfred Giles, a prominent English architect, to design a school. Built in 1893, the Morris Ranch Schoolhouse, with its sharp pointed gables and tall central spire towering above the oak trees, looks like Camelot or a castle on the Rhine.

After work hours, Morris Ranch had a vibrant social life. Partners two-stepped and waltzed across the dance floor upstairs at the general store. The school hosted musicals. Mrs. Albert Morris organized a drama club and a Shakespeare club. The English miller, R. B. Everett, rode the Liberty Float in the Fourth of July Parade each year dressed as Uncle Sam.

While the people at Morris Ranch lived well, the horses got the best of everything. Trainers worked them hard but pampered them like grandchildren. The enormous airy horse barns, each one a city block long and as big as a cathedral, had 30 stalls with hot and cold running water. Every year the most promising one-year-olds traveled from Kerrville to the east coast in padded railroad cars.

Morris Ranch also supported its Hill Country neighbors. Its horses raced at the Gillespie County Fair. Morris Ranch built the first stables and tac rooms at the old Gillespie County fairgrounds.

John Morris first saw a 12-year-old Fredericksburg jockey named Max Hirsch at the Gillespie County Fair in 1892. Morris hired Hirsch as an exercise boy. Max Hirsch later became a legend as the trainer of 3 Kentucky Derby winners. “Assault,” a horse trained by Hirsch and owned by the King Ranch stables in South Texas, won the Triple Crown in 1946.

The racing business thrived until several states, among them Texas and New York, passed a wave of anti-racing laws in the early 20th century. Racetracks closed. After 1902 the Morris family sold its horses, ended its breeding and training programs and leased its property to tenants for farming and ranching. By 1931 the family had sold off all but a few acres of the original ranch.

Then, as the years passed, the community of Morris Ranch lost its energy and vitality. The roller mill shut down after World War I. The cotton gin went out of business after the boll weevil damaged the cotton crop. The post office closed in 1954, and the store soon after that. Morris Ranch school consolidated with Fredericksburg in 1962.

Although Morris Ranch closed its gates a century ago, it left a mark on this part of the world. Not only did it elevate Gillespie County’s appreciation for fine horseflesh, it introduced isolated Hill Country communities to different cultures and faraway places. It opened a window to the world for people of Gillespie and Kerr Counties.

The story of Morris Ranch is both fleeting and timeless. Visitors still feel the ranch’s ghostly presence in the ruins and abandoned buildings scattered along Morris Ranch Road. Even today it inspires and mystifies.