A U.S. Army ambulance pulled by four mules skidded to a stop in the mud bringing Herman Lehmann home to Loyal Valley after eight years with the Indians. As the rain fell, a curious crowd closed in, talking excitedly in a language Herman no longer understood. Through it all he sat quietly in the wagon, staring straight ahead into the darkness.

Then the crowd parted, and a woman came forward. Her face was familiar, but the years had erased the memories. He stayed glued to the wagon seat until the officer in charge ordered, “Get out and kiss your mother.” He climbed down, and she led him to the light. Unsure until that moment, she knew he was her son the instant the rays of the lamp fell upon him.

But it wasn’t a happy ending. Freed from captivity, Herman became a prison of two worlds. He lived in one world but could not let go of the other. He was a captive of civilization as surely as he had once been a hostage of the Indians.

The son of German immigrants, Herman Lehmann spent his early life on Squaw Creek, between Doss and Cherry Spring, in southeast Mason County. Even today Squaw Creek is somewhere off the charts. In the 1860s it was on the fringe of the civilized world. It was lonesome, remote and dangerously exposed.

Out on Squaw Creek, Herman was an interloper among the coyotes, armadillos and rattlesnakes. He hadn’t been to town too often. The young boy had no friends outside the family to play with. He had never been to school or a church. He was illiterate. He spoke only German. He was painfully shy and uncomfortable around strangers. On the rare occasion a traveler drifted off course and wandered by the home place, Herman hid in the barn until the traveler wandered off again.

Then one day, without warning, life took a sharp left turn. In May 1870, ten-year-old Herman, his younger brother Willie and his two younger sisters were 300 yards from the house, scaring birds out of the wheat field. There was a rustle in the brush and a dust cloud.

As sudden as the strike of a rattlesnake, an Apache seized Willie where he sat. The girls got away. Herman ran, but two Apaches wrestled him to the ground, then tied him to the back of a wild Indian pony.

In the rush to get away the Apaches and their captives crossed Squaw Creek and climbed the bluff on the other side. They galloped through Loyal Valley, continuing on to Moseley’s Mountain at a dead run before turning northwest toward their camp in the mountains of New Mexico.

Willie escaped, traumatized but alive, and in a few weeks was back in Loyal Valley. Herman, believing his family was dead, no longer had a home.

In the Apache village Herman began a brutal but effective initiation into Apache life. He learned the language, rules and customs of the tribe in record time by a strict system of punishments and rewards – heavy on the punishments. Captives had to learn quickly or die.

In time Herman earned the guarded trust of his captors. He became an Apache, and the tribe became his family. He took part in bloody raids on settlements in Texas and Mexico. He fought the Texas Rangers and the cavalry. He was especially vicious because he had to continually prove himself.

Then just as he reached a level of acceptance with the Apaches, he killed a medicine man in revenge for the death of his mentor and had to flee for his life. He wandered alone in the wilderness for a year. In lean times he ate raw skunk and drank muddy water.

He took up with a band of Comanches. He got to know Quanah Parker, who later adopted him.

He lived with the Comanches until the army forced the tribe to the reservation. In 1878 a captive recognized Herman. The authorities ordered that he be returned, under guard, to his family in Loyal Valley.

Compared to life in a Comanche camp, the daily routine in Loyal Valley was unimaginably dull. Herman amused himself by killing his neighbor’s hogs and stealing horses. He scared the daylights out of children and enjoyed it. “I would give a yell and draw my bow on them,” he told writer J. Marvin Hunter. “For a while that was the only real fun I had.”

White man’s clothes were uncomfortable. He sometimes embarrassed his family by going out in public, all painted up, dressed only in leggings, a breechcloth and feathers. He refused to sleep in a bed, sleeping instead on the ground outside his mother’s Loyal Valley hotel and stage stop.

He went to church for the first time, but it didn’t go well. When the shouting and singing started, Herman thought the congregation was praying for rain. He gave a Comanche yell, leaped over pews and did a rain dance.

His family called him “Herman,” and the word sounded familiar. Then slowly, painfully, the fog lifted and some of the old memories returned. “The wildness,” J. Marvin Hunter wrote, “gave way to a kind of noble nature.”

He never fully adjusted to white society, but he did his best. He accepted his role in the community. He relearned German and even learned to speak English. He went to school one day but never went back. He married and had children.

He was a teamster and a cattleman, but the complexities of the financial system baffled him. He opened a saloon at Cherry Spring, a forerunner of the Cherry Spring Dancehall, but he was no businessman. He drank too much and had to sell out.

With help from Quanah Parker, the United States Government placed Herman on the tribal rolls and gave him 160 acres on the Comanche reservation near Fort Sill. After that he and his family spent extended periods of time in Oklahoma.

In Texas he was a celebrity. He was a star attraction at county fairs and rodeos where he gave exhibitions of his considerable skills at riding, roping and archery.

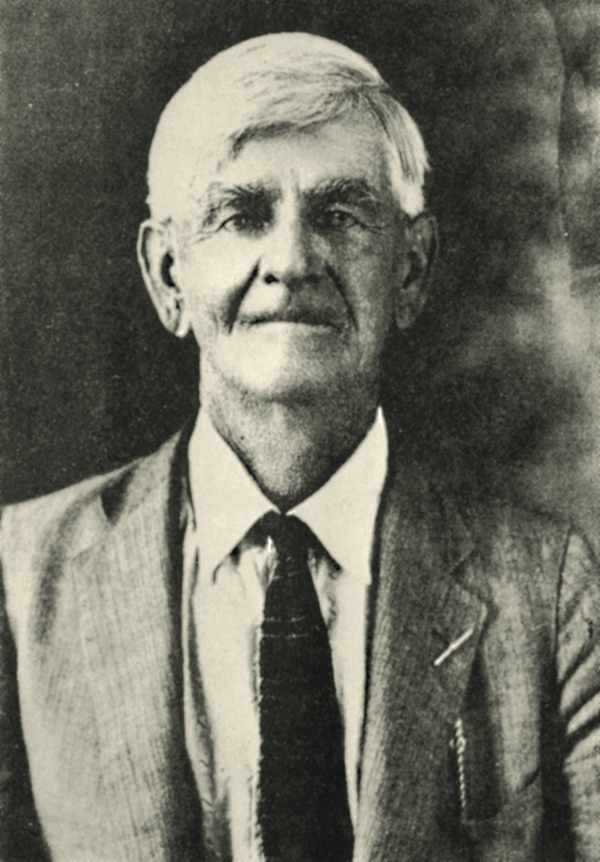

He was a proud man, and he impressed everyone he met with his sense of humor and friendliness. As he grew older he especially enjoyed good-natured reunions with trail drivers and ranchers whose livestock he had stolen.

But there was anguish below the surface. He searched for happiness but never found it. Estranged from his family in Oklahoma, he died of pneumonia at brother Willie’s ranch on February 2, 1932. Willie buried Herman at the cemetery in Loyal Valley.

Fate dealt Herman Lehmann a terrible blow, and he never recovered from it. The story of his capture, his desperate fight for survival, his brutal conversion to Native American culture and his reluctant return to his birth family in the Texas Hill Country, is a frontier classic. It is both remarkable and tragic.

Suggested reading – The Last Captive by A. C. Greene