The Easter Fires Pageant unfolded like scenes from a Disney movie. Silver Arrow, the Indian brave who learned Christianity from the Spanish, saves Princess White Fang from being roasted at the sacrificial fire to the rain gods. Enormous rabbits make tie-dye Easter eggs. Fredericksburg High School Band Director Tom Rhodes, dressed in a bunny suit, directs the Bunny Brass Band with a carrot.

The story of Fredericksburg’s Easter Fires is more than a celebration of the most important Sunday in the Christian world. It is part folklore, part show biz and part fiery ritual from a dark pagan past. It is both a sacred religious ceremony and a Hill Country fairy tale worthy of the Brothers Grimm.

The burning of brush fires on hilltops in the springtime was a custom in Europe for thousands of years before the Germans came to Texas. The fires were part of a pre-Christian ceremony that heralded the end of winter and the coming of spring. Villagers believed the fields would be fruitful and the houses would be spared sickness as far as the firelight could be seen.

Fire was front and center in those early celebrations because it was so crucial to human development. For millions of years humans found warmth and security in front of a fire. An attraction to fire is burned into our DNA. That’s why we have fireplaces.

Only in more recent times, the last 1,700 years or so, did burning fires on top of hills become associated with Easter.

Early Christians celebrated Easter, the day Jesus rose from the tomb, at different times until the year 325 when they set the date as the first Sunday following the full moon that comes after March 21. This relation to the vernal equinox meant that the celebration of Easter now coincided with the pagan spring festival. Over time, the two events merged.

As Christianity spread over Europe, Bishops tried to stop the pagan rituals, including the burning of fires on the night before Easter, but the old ways hung on in parts of Europe, particularly in some of the German states.

Many other modern-day Easter traditions are carryovers from those early Christian and pre-Christian days. Because eggs were not on the menu during Lent (the 40 days of fasting and prayer that begin on Ash Wednesday and end the following month on Holy Thursday), early Christians gave colored eggs as Easter gifts. Even the rabbit, an ancient symbol of fertility, is a remnant of our pagan past.

When the Germans came to the Texas Hill Country in the mid-19th century, they brought these traditions with them. Evidence suggests that the Germans built fires on hilltops to celebrate Easter since the founding of Fredericksburg, and they kept the ancient tradition alive year after year.

Leading up to the big day church groups, school children and families hauled brush, old tires and just about anything that would burn to the top of Cross Mountain, Lehne’s Hill, Kordzik’s Hill and other elevated spots on the outskirts of town. Then at sundown on Easter Eve, as the Abendglocken (evening bells) rang out at churches all over Fredericksburg, huge roaring flames lit up the night sky, casting ghostly shadows and throwing sparks like fireflies hundreds of feet in the air.

In the early years the Easter Fires celebration was not well known outside the Hill Country. Then in the 20th century, word of this unique Fredericksburg tradition slowly spread along the grapevine to the outside world.

Articles describing the Easter Fires appeared in San Antonio newspapers in the 1920s and ’30s. In 1940, The Texas Quality Network announced the event over San Antonio’s WOAI Radio. The publicity attracted visitors who trickled in to watch the ceremony.

Since their earliest days in Texas the Germans told stories to explain the origins of the Easter Fires which had always been a mystery. Those stories took numerous twists and turns as they passed down through the generations. On April 13, 1939, the Fredericksburg Standard published what may have been the first written version of one popular Easter Fires legend.

The story suggests that while the origins of the Easter Fires were in Germany, “the fires in Fredericksburg began when a local man, probably around the date of the founding of the colony in 1846, started a fire on a hillside and came back to tell his children that the fire had been started by the Easter Rabbit for the purpose of boiling and dyeing the eggs that he was to leave in the children’s nest the next morning.”

That legend became a special project for Bill Petmecky, the Fredericksburg Postmaster. Petmecky wrote stories about the Easter Fires legend, and he conceived the idea of an elaborate Easter Fires Pageant to go along with the lighting of the fires on Easter Eve.

The first Easter Fires Pageant took place on March 27, 1948 at the Gillespie County Fairgrounds. Petmecky wrote the script based on Spanish myths, Indian folklore, stories of the early settlers and a variation of the local legend of the Easter Bunny lighting the fires to dye Easter eggs.

Petmecky’s version of the Easter Bunny story takes place on the Saturday night before Easter 1847. John Meusebach, the founder of Fredericksburg, and most of the men are on the San Saba River negotiating the peace treaty with the Comanches, leaving the women and children at home with little protection.

Suddenly, just after dark, fires appear on several hills north and west of town. The Indians are close by, watching the village and using the fires as a form of communication.

In a cabin near Fredericksburg, a pioneer mother and her children watch the fires from the window. The children are frightened so the mother quickly makes up a story to calm their fears.

She tells her children that the Easter Bunny built the fires to cook Easter eggs in large kettles and that little rabbits of the hills gathered wild flowers to make the dye that colored the eggs.

The story quiets the children, and they soon fall asleep.

A few days later Meusebach and the men return to Fredericksburg after negotiating the peace treaty with the Comanches. On hearing the pioneer mother’s story, the men make a promise to keep the Easter Fires tradition alive.

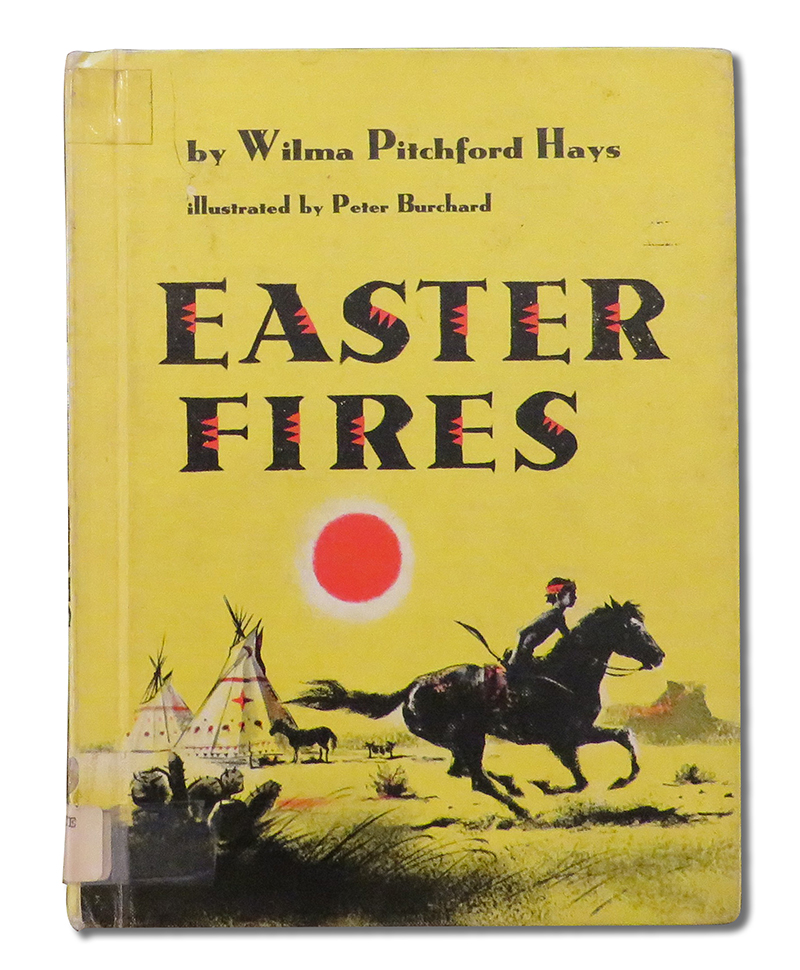

The legend of the Easter Fires inspired a number of children’s books. One of the first was Siddie Joe Johnson’s Rabbit Fires, published in 1951.

In 1952, Petmecky published his version of the Easter Fires legend called “Legendary Tales – Easter Fires of Texas” later changed to “Easter Fires of Fredericksburg.”

Meanwhile the reenactment of Petmecky’s “Easter Fires of Fredericksburg” drew big crowds. By the 1970s, a 600-member cast of local volunteers performed the pageant for thousands of visitors from around the world. Then, after dark, the lights dimmed, the church bells rang and all eyes turned to the glowing hills to watch the flames dance against the night sky like a giant movie screen.