The evening news with Walter Cronkite wasn’t good 50 years ago. There was war in Vietnam, rioting in the streets and a break-in at the Watergate Hotel. OPEC slashed crude oil production. The price of gasoline skyrocketed to 50 cents a gallon. The Monkees broke up.

Then, just when it seemed the world had lost is sense of humor, an eccentric band of pranksters took over Luckenbach and made us forget our troubles. They made us laugh again. They elevated leg-pulling to an art form. How Luckenbach made the jump from a wide spot in the middle of nowhere to the Texas capital of high jinx and horseplay is a story with more twists and turns than the Cain City Road.

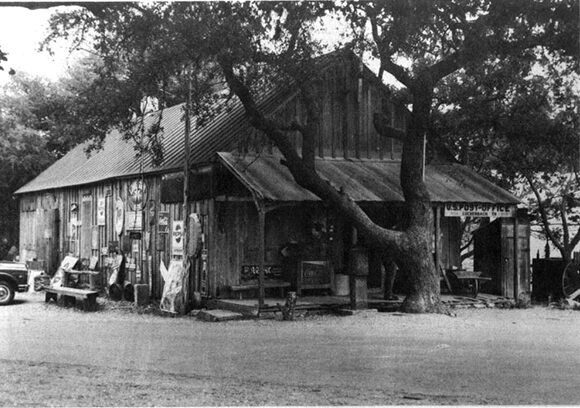

Even today Luckenbach, located on South Grape Creek 13 miles southeast of Fredericksburg, is so small it’s barely visible. It dates to 1849 when the Engel family established a trading post there. August Engel built the combination general store, post office and saloon in the 1880s. His daughter Minna reportedly chose the town’s name to flatter her fiancée Carl Albert Luckenbach. By the 1890s, the town included a steam-powered cotton gin, a blacksmith shop, a dancehall and a few outbuildings.

For almost a century the store, post office, saloon and dancehall did just enough business to stay afloat. Then around 1970, the post office closed and Benno Engel put the entire town up for sale. Hondo Crouch, Guich Koock and silent partner Kathy Morgan snapped it up like costume jewelry at a flea market.

“I saw a little ad in the Fredericksburg paper that said ‘town for sale,’” Guich said, “and I always wanted one so I got with Hondo and we bought it. We tried to buy Dallas,” he added, “but it wasn’t for sale.”

The new owners planned to keep the town more or less as it was. Hondo Crouch envisioned Luckenbach as a place to drink beer, play dominoes and not work.

The town was not well-known back then. Days were quiet. Visitors were rare. One day a regular who hadn’t been to Luckenbach for several weeks asked Hondo for the news. Hondo thought awhile. “Well,” he finally said. “The potato chip man came by.”

Back then Hondo, Guich and their buddies had Luckenbach all to themselves. They would gather under the oak trees to drink beer, tell lies, play music and let their imaginations run wild. Hondo imagined Luckenbach as an independent municipality – like the Vatican. He appointed himself the mayor. Kathy Morgan was the sheriff. Roy Petsch was the Agricultural Commissioner. Hondo even appointed ambassadors to foreign countries. The rules at those early gatherings were simple. Bring your sense of humor and check your differences at the cattle guard. Having fun was the common denominator.

Occasionally a country singer, a minor movie star or a politician would drop in just for fun. For a time, Luckenbach was the Hill Country’s best kept secret. The secret got out after the organizers of the Chilympiad in San Marcos decided to exclude women from the world championship chili cook-off. That faux pas opened a door of opportunity wide enough to drive a beer truck through. Seizing the moment Hondo and Guich organized the Women’s Only Hell Hath No Fury Susan B. Anthony Memorial Bowl of Red Chili Cook-Off scheduled for October, 1971 in downtown Luckenbach. Word of the event spread like a conspiracy theory, especially after Frank X. Tolbert wrote an entertaining column about it in the Dallas Morning News. Other newspapers across the country picked up the story. Several thousand people showed up. That event put Luckenbach in the regional spotlight. Curious folks began driving in from Austin, Dallas, San Antonio and Houston for beer, music and a little good-natured nonsense. The potato chip man came by more often.

Of course getting to Luckenbach wasn’t always easy for the first-time visitor. The town was so small it wasn’t on most maps. The Highway Department put a sign out on the highway, but people kept stealing it. Meanwhile Hondo, Guich and a growing cast of free spirits were always dreaming up stunts, like the Luckenbach World’s Fair and the Mud Dauber Fest, hoping to draw a sizeable crowd to town and sell a few extra cases of beer. The World’s Fair began as an elaborate joke, but the joke backfired. Ten thousand people showed up. The store ran out of beer. There weren’t enough toilets – or trees. The crowd was so big it scared the livestock. The cows stopped giving milk, and the chickens quit laying eggs. The guineas disappeared entirely.

But the people had a ball, as best they could remember. Events included a spitting contest (for distance and accuracy), a cow chip tossing contest, a championship chicken-flying contest, a laughing contest, thoroughbred armadillo races and live music courtesy of Willie Nelson and Jerry Jeff Walker.

Hondo Crouch made the rounds dressed in his regular uniform: a sweat-stained cowboy hat, red bandana, wrinkled shirt and faded blue jeans stuffed inside a pair of scruffy cowboy boots. As one visitor put it “Just looking at Hondo puts you in a good mood.” No one knew what to expect from Hondo. One day he showed up in a suit. He said he ran out of dirty clothes.

With a windfall of beer money the town made a couple of concessions to the modern world. One was plumbing. The other was a parking meter. Not that anyone ever paid to park in Luckenbach, but every once in a while a drunk cowboy dropped a quarter in – thinking it was a slot machine.

Except for Hondo and Guich, no one did more to promote Luckenbach than Jerry Jeff Walker. In 1966, Jerry Jeff (real name Ronald Clyde Crosby from Oneonta, New York) met musician Dow Patterson in Austin. Patterson, who was Hondo Crouch’s son-in-law, introduced Hondo to Jerry Jeff. Hondo made an easy connection with restless souls like Jerry Jeff. A lifelong friendship began the instant they met. “Hondo was just this magical character,” said singer Gary P. Nunn who played in Jerry Jeff’s band. “Everything he did was enchanting, humorous and playful.”

In August 1973, Jerry Jeff Walker recorded an album before a live audience at the old dancehall in Luckenbach. That album, “Viva Terlingua,” captured the magic of the place and inspired a generation of Texas songwriters, musicians and poets.

With each event the reputation of Luckenbach grew. The weekend crowds got a little bigger. The celebrations got a little crazier. A few more celebrities showed up, drawing media attention to this tiny Hill Country village. Then in 1977, Waylon Jennings, joined by Willie Nelson, recorded a song called “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love),” written by Chips Moman and Bobby Emmons, neither of whom had ever been anywhere near Luckenbach. The song shot straight to number 1 on the country charts and number 25 on the Billboard Hot 100. Suddenly anyone on the planet within earshot of a radio knew about this magical place called Luckenbach. That song made the town world famous and solidified its reputation as a legendary watering hole for musicians and artists and a refuge for old hippies looking to relive their misspent youth.

It’s now been 50 years since the over-active imaginations of Hondo Crouch and Guich Koock created Luckenbach. Today the cast of characters is different, but the spirit of the place hasn’t changed a lick. People have been finding common ground here for half a century. “Luckenbach represents everything Americans long for,” the town’s former Press Secretary Jack Harmon once explained. “People dream about the tranquility and easy-going atmosphere that exists in Luckenbach.”

“Hell, this place is different. The whole world changes when you get here.”

How does Luckenbach maintain its sense of humor in a modern-day world of extreme political polarization? “Luckenbach is a logic-free zone,” says Historian/SOMEBODY Virgil Holdman. “We don’t talk politics or religion. There’s no television. There’s not much to do here except get to know each other. Every day we have cowboys, bikers and city slickers at the bar, and they come to here for one reason — to have fun. That why Luckenbach exists.

“There’s no place like this in the world.”