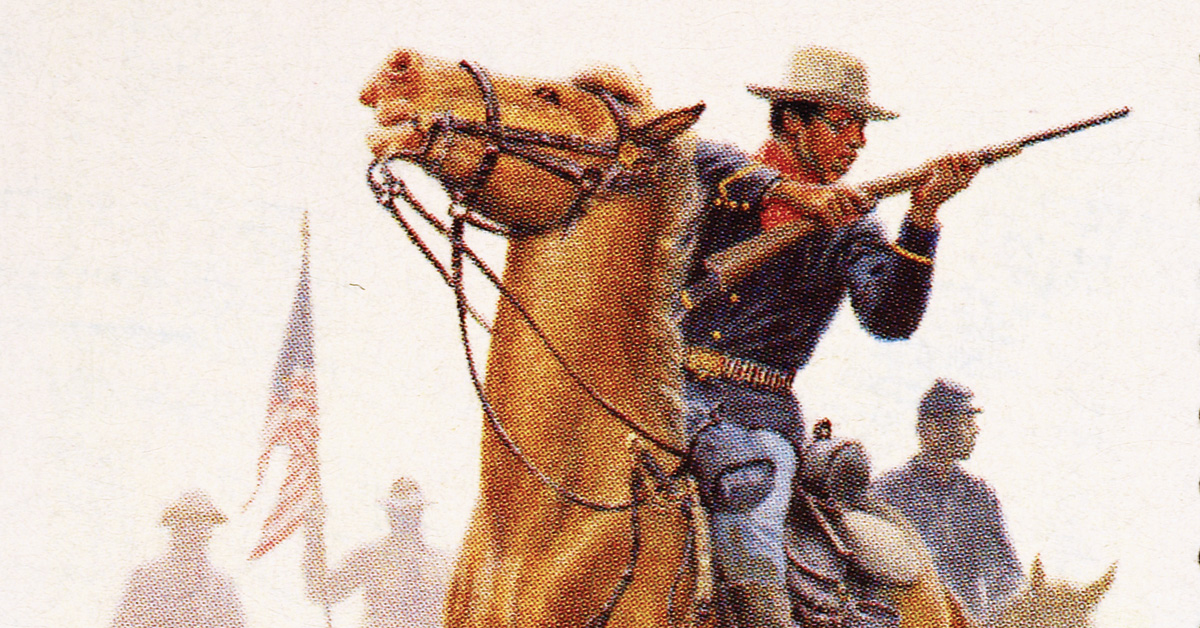

The Plains Indians named the fighters because of their dark skin and curly hair. And African-American regiments, tabbed “Buffalo Soldiers,” fought alongside white troops to help settle the American West. At outposts established by the federal government, these often overlooked soldiers battled hostile forces and helped usher residents into the vast, unsettled region.

The U.S. government established 22 outposts around Texas to help usher in and protect settlers. After the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation, Black troops saw a newfound mission away from slavery’s demeaning existence.

Many of these soldiers had seen action during the Civil War. Around 180,000 fought with Union troops and a few thousand even fought for the South. But after all previous conflicts, Black troops had been sent back into slavery. When the Civil War ended, some drifted west to become farmers, cowboys and settlers.

“For most, it was a dream come true. No more cotton fields, no more factories, and $13 cash every month, regular meals, a uniform and a chance to be somebody,” the 1992 documentary “The Buffalo Soldiers” stated.

These fighting men had to overcome prejudice from both within the military ranks and also in the communities where they were stationed. White officers commanded the regimens, sometimes receiving a bonus for “having to serve” with them. General Custer was believed to have said, “No thanks. I don’t want to serve with no brunettes.”

But they were in demand as hostile Native Americans populated much of the west all the way to California, hampering its settlement. Texas was no different with residents of new settlements, like Fredericksburg, witnessing kidnappings and killings.

So they helped build forts, scouted, escorted wagons and surveyors. And they fought and fought hard. Up to 20% of the entire cavalry were black during the late 1800s. Though the white soldiers may have chuckled at the name bestowed upon them by the Natives, the name was actually an honor with an animal they revered and helped them survive. The Buffalo Soldiers themselves took pride in their moniker, in their fight and their skills.

In 1990, recognizing that these fighting men were still mostly overlooked, General Colin Powell helped establish a monument in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, recognizing their achievements. A painting of a Buffalo Soldier hung in Powell’s office at the Pentagon to remind him of “the thousands of African-Americans who went before me and who shed their blood and made their sacrifices so that I could sit where I sit today,” the Los Angeles Times wrote about the dedication ceremony.

Texas Parks & Wildlife Department started a program with a reenactment group to preserve the history in 1996. Today, they offer reenactments around the state at several different state park sites.

Kevin Malcolm is the educator and curator for Fort McKavett State Historical Site, located just west of Menard. “The Buffalo Soldiers’ history is intimately connected with Fort McKavett,” Malcolm said. “They were an integral part of rebuilding, repairing and expanding and were a significant force for good in West Texas following the Civil War.”

The story of the Buffalo Soldiers is one of heroism and duty, yet one largely overlooked in history. Fortunately, the story is being kept alive by dedicated reenactors and history enthusiasts.

Fort McKavett

www.thc.texas.gov/historic-sites/fort-mckavett-state-historic-site

7066 FM 864 • Fort McKavett, TX 76841 • (325) 396-2358

Open daily 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., except for major holidays. (Call ahead for possible changes due to coronavirus safety practices.)

Malcolm’s book recommendation: “The Buffalo Soldiers: A Narrative of the Black Cavalry in the West,” by William H. Leckie.