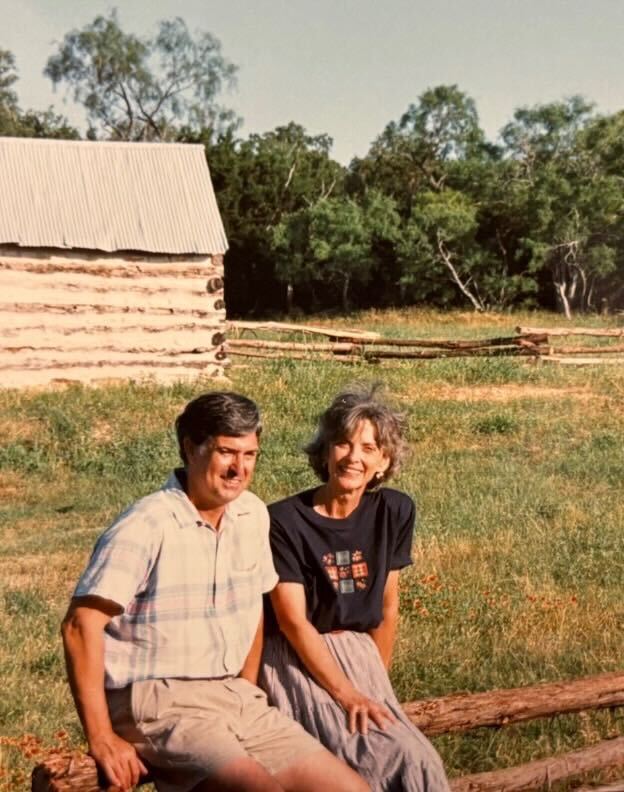

Dr. Richard and Bunny Becker bought land near Fredericksburg in the early 1990s, seeking a rural weekend escape from San Antonio. As they got exposed to the tiny Hill Country wine industry, they began to dream. Little did they know the winery they established over the next few years would grow into a cornerstone operation and they would educate and inspire others to follow their own passion. Three decades after their first harvest, Dr. Becker and his crew will host a year-long celebration on times of plenty, times of trial, and the growth of wines recognized as world-class.

Becker became just the third winery in Gillespie County, joining Bell Mountain, owned by the late Bob and Evelyn Oberhelman, and Grape Creek, begun by the late Ned and Nelda Simes and later purchased by Brian Heath. A fourth winery, Vernon and Kathleen Friesenhahn’s Sister Creek Vineyards, was in neighboring Kendall County. Becker’s state winery permit was No. 29, and there were only 10 active Texas wineries at the time. Today, Becker Vineyards is a legacy winery among more than 700 Texas winery operations.

Their venture began with 46 acres, an appreciation for fine wine, and a tenacity to learn something daily and apply it to the operation. Becker, an endocrinologist by trade, initially served as winemaker, later bringing on world-class talent. Bunny, a speech therapist, helped guide the operation from its early days of producing 2,500 cases a year to over 85,000 per year today. Currently the estate vineyard has 70 acres, and the total property has grown to 369 acres.

“When we first started, we planted all five red Bordeaux varieties and Sauvignon Blanc. I was thinking this would be a Bordeaux area. And we planted Chardonnay. I really didn’t know what I was doing — I was reading books,” he admitted. “So we made the Chardonnay, and we put it in new French barrels — we had maybe 20, not a huge number — and we kept it in the barrel for a year. Then I put two egg whites in the top of each barrel to let it fall through to soften the wine and bottled it. And we won a gold medal in the Dallas Morning News Wine Competition. They asked if I would come and speak about it, and I told them, ‘All I know is what I learned in books, but I’ll bring the wine.’”

Viognier came with the second harvest and put the young winery on the map. The Beckers poured it in the Austin Food & Wine Fest in 1997 where Robert Mondavi was the celebrity winemaker. Becker was among 20 wineries vying for attention at The Four Seasons Restaurant. Mondavi, Becker said, came straight to his table and said, “I want to taste your wine.” Becker served up the Viognier and Mondavi questioned him for 45 minutes. “About 30 minutes in, I realized he was suspicious that we hadn’t made the wine, thinking a wine this good couldn’t be made in Texas. But if you’ve grown the grapes and made the wine, you had all the answers he was looking for. At the end he said, ‘You made this wine. Keep it up.’” Mondavi later purchased that Becker wine at auction, and the next day his photo was in the Austin American-Statesman holding the Becker Viognier. “That was a good day,” Becker said.

Mondavi invited the Beckers and his team to his California winery and made available any and all parts of the operation. This Texas wine origin story is similar to California’s when the Golden State wines caused an international ruckus by winning the Paris Wine Tasting in 1976. Today, Texas is making its mark as the second most popular wine-destination behind Napa Valley.

Grounded

Becker is still spry at 83 (as evidenced by his ascension of the winery’s front wall for the cover photo), a walking billboard for the health benefits of vino.

“I’ve always wanted to have this view to the west,” he said from a comfortable, open-air pavilion where hundreds come to sip on weekends. “There is a field of poppies coming up, and over there is lavender. And we have grapevines and we’re planting more grapes in the back. Our goal is to have 100 acres of vines in the ground.”

Over the years, they added the large tasting hall and the Lavender Haus Reception Hall, a replica of the LBJ Settlement Barn in Johnson City. An original log cabin also stands, refurbished a year after the tasting room opened. Another building, The Barrell Shed, is used for wine club receptions. In the private wine cellar, he points out mesquite-wood tables crafted in Mexico.

The busy staff now hosts over 80,000 tastings each year and Vine Ops and other hands tend to plant in the growing vineyard acreage.

“My goal has always been pretty grandiose,” Becker said, looking back. “I want to make wine that will compete with the best wines in the world. That’s a big challenge.”

The Beckers were determined to improve their own wine, but they also openly shared knowledge and helped build a camaraderie among the region’s industry pros and a vision of what the region could become, even with its early, admittedly poor, reputation.

Bunny Becker, considered a Grande Dame of Texas wine, passed in 2019 from cancer but left her indelible mark. The couple met on a blind date at the University of Texas in Austin. She stood 6 feet, and he measured 6-feet-6. They told people they “matched in altitude and were together thereafter in attitude.” Bunny would personally carry wines to local restaurants in the early days, and her grace encouraged many a new entrant to the industry. She also began the popular Lavender Fest at the winery. Her spirit is remembered today through the Bunny Becker Women in Wine Award, given three times, the first to Texas Tech Enology Professor Maureen Qualia, the second to Roxanne Myers of Lost Oak Winery in Burleson, and the third to Denise Clark oof Texas Fine Wine.

Steady team

Walls in the main tasting room show framed White House menus which served Becker wines in the Clinton, Bush, and Obama administrations, as well as for the King and Queen of Spain. Others show menus from James Beard dinners, where the wines were served with Texas chef pairings. But it wasn’t always so.

Marketing Manager Nichole Bendele stopped by the winery to apply for a part-time job in 1996 and has been with Becker ever since. “I remember people kind of laughing, like ‘What do they think they’re doing?’” said Bendele, also a Level 2 sommelier. Foot traffic in those days was “on the lighter side,” she said, with most visitors searching out peaches or antiques. But local restaurants began serving local wines, helping promote the industry. “Dr. Becker always wanted to make the best possible wine. He didn’t cut any corners and focused on quality,” she said. “When he first started out, some people told him Texans only drink sweet wine. But he and Bunny already had wines from around the world. They made wine in the style they liked to drink, and then we had a huge influx of people looking for that. And there’s more than a little bit of that spirit of no one is going to tell a Texan what he can’t do.”

People began looking for a wine destination, and the Beckers encouraged it. “As other wineries have come in, it’s been exciting to welcome these people who are passionate about making wine. The same people that thought it was funny at first became wine drinkers and then also became unofficial ambassadors, promoting the area.”

Jon Leahy, who had worked for top California wineries, came on board in 2012 and upped the game. “I sent Jon a case of 12 of our wines,” Becker recalled. At the time, Texas wines were not well-regarded in wine circles — and, honestly, they needed time. But Leahy remembers while he knew the winemaking could be improved, he liked the fruit. “It was high-quality,” he said.

Leahy brought his vast industry knowledge. Even during a staff tasting, he uses glass toppers as opposed to plastic to make sure there is no effect on wine scent. He knows the exact percentages of blends, and he discussed the effects of potential tariffs on shipping.

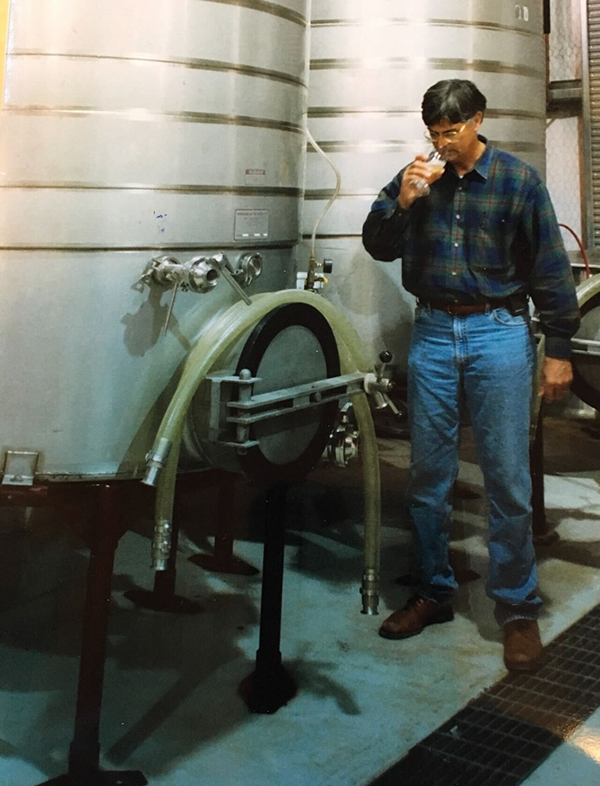

On a recent visit, Becker and staff tasted 2023 red blends aged in barrels but only halfway to bottling. Becker swirls, sticks his nose far down into the glass to get the aromas. “When I first started making wines, I’d see pictures of French winemakers doing this and I thought it was an unnecessary affectation. Turns out it’s everything.” He jokes that years ago, he stopped swallowing that wine during tastings, and quipped, “That’s greatly improved my ability to make reasonable judgements.”

Becker also joked about deferring to Leahy’s expertise. “Jon makes about three passes once he gets near bottling. He does this very democratically and lets us make a choice, and then he does whatever he wants. This is called humoring the old man.”

Good fruit

Yet there is no arguing the results. Today Becker Vineyards has won 110 Double Gold and 160 Gold medals from the San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition, the San Francisco International Wine Competition, and others. “That just shows you the winemaker is important,” Becker said. “These are all rarified palettes, and they’re picking our wines over those on the West coast. It’s Jon’s winemaking, but it’s also the fruit.”

Good fruit is produced on good land, and that’s where Becker’s knowledge and prescience paid off. “We talk about the terroir. It’s certainly the air and water, but primarily it’s the soil. It’s a blend of sand and eroded pre-Cambrian granite … formed from ocean sludge 500 billion years ago. It’s not on the surface in many places on the planet. But the Llano Uplift pushed it up. The calcareous subsoil that we call caliche is very important to wine richness. I think the opportunity to grow more good wines here is great.”

The barrel also brings much to the wine, Becker learned early, and Leahy concurred. The winery uses white oak with subspecies from different sources, both in Missouri and abroad in France. And the less-expensive domestic varieties don’t always equate to the right choice.

A half century removed from California wineries’ surprise wins in France, Texas wine has grown and improved and become respected on the global table. Better education for winemakers has much to do with it, but the Texas terroir in the High Plains and the Hill Country is key.

Educators, encouragers

Bendele says Becker is seen as a resource, confidant, and sage for others in the industry. “In the early days, we did a bunch of equipment sharing because it was expensive. And he’s always shared information freely with visitors or winemakers from other states or countries. He also taught English at a college level, so education has always been very important,” she said.

Kim McPherson, owner of McPherson Cellars in Lubbock and a second-generation winemaker, said Becker is “a class guy who’s always done a great job. Bunny was such a nice person as well.” McPherson said it was Becker who introduced him to Pat Brennan, who later became a partner in 4.0 Cellars, now called Texas Wine Collective. He also credits Becker with discovering a certain grape would grow well in Texas soil. “I credit him for getting Texas on the Viognier craze because he was a pioneer. That has helped me a lot, as well as anyone else who makes Viognier.”

Dr. Bob Young, another retired medical doctor turned winemaker, who owns Bending Branch Winery in Comfort, said the Beckers were key to him entering the industry. He wanted a creative outlet after his medical career, and Becker welcomed him to the winery one day and gave him a cellar tasting. “He talked about the opportunities and challenges. He was very straightforward about how difficult the business is, but at the same time, encouraging. That sealed it for me,” said Young, who now owns two well-regarded estate wineries. And Becker has continued to share input and advice. “He deserves so much credit for what he has done. I consider him the godfather of the Hill Country wineries.”

So what do the next 30 years look like for Becker Vineyards? Both of the Becker sons have expressed an interest in taking over, though they’re living their own lives. Joe is a medical school professor and endocrinologist, and son Will teaches math in Massachusetts. Six years after Bunny’s death, Becker in December married Margaret Byer, who has a background as a fashion buyer.

For now, the good doctor is enjoying the fruits of his labors and those of his devoted staff. “We’re going to get past this early, mediocre history in Texas wines. I think there’s really something in the fruit, and that’s getting discovered,” he says. “When people have confidence that they’re working with fruit that’s equal to that from Bordeaux or Napa, it will take a great step.” And Becker will continue to have a hand in an anchor operation of the state’s still-growing industry.