Even while confronting the uncertainty, the loneliness and the physical hardship of the harsh Texas frontier, an extraordinary group of German Freethinkers in the Texas Hill Country still found time to enjoy the music of Mozart, conduct spirited community forums in Latin and savor a bottle of good wine.

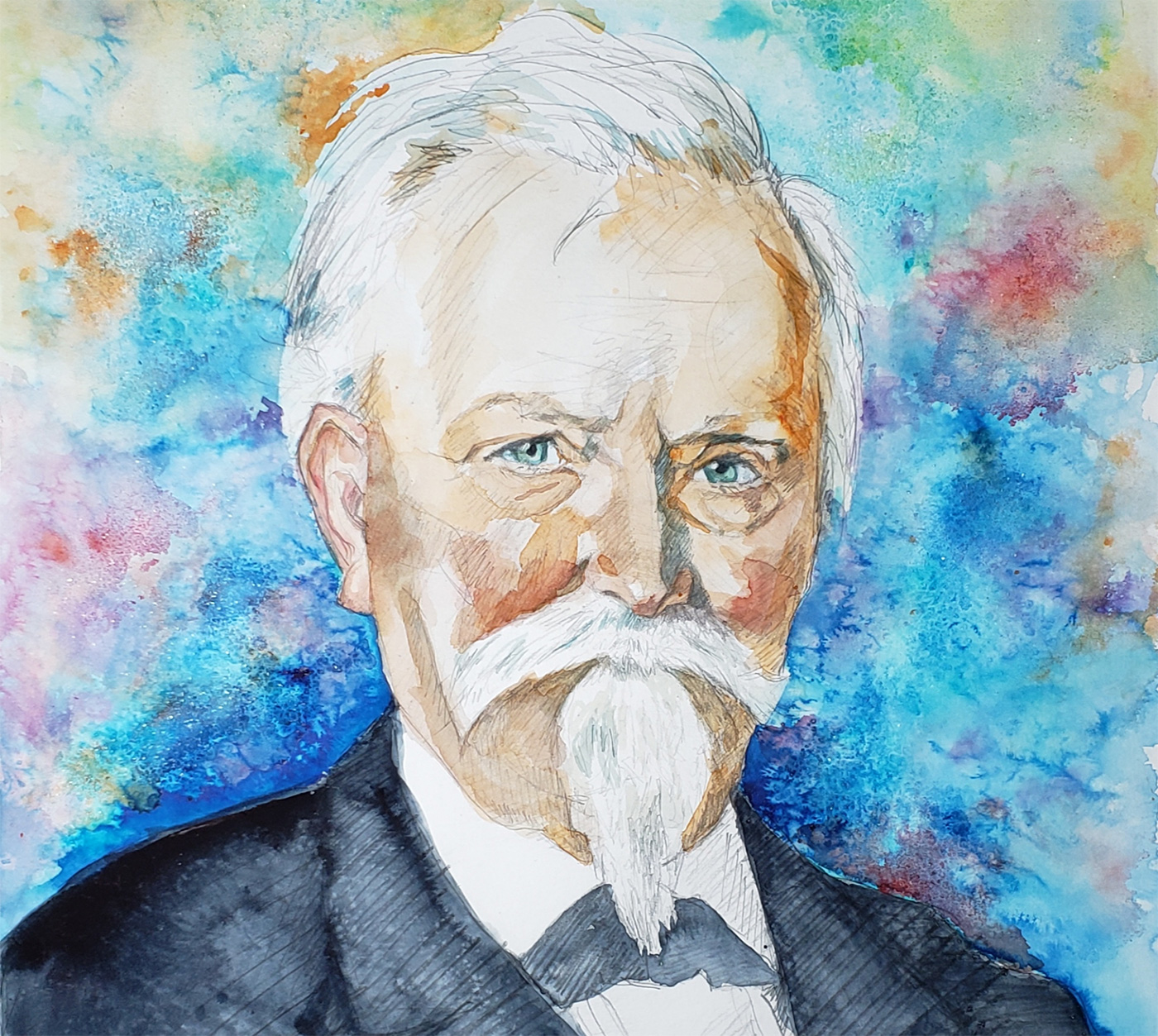

Between 1845 and 1861 a number of German Freethinkers (Deutsche Freidenker) arrived on the Texas frontier. They were not typical working-class immigrants but educated German intellectuals, many from the wealthy class.

Freethinkers were part of a European reform movement with roots in the Enlightenment. They opposed despotism, class privilege and the excessive power of the church.

They advocated unorthodoxy, religious dissent, skepticism and unconventional thinking. They believed that truth came from logic, reason and empiricism not from authority, tradition or dogma.

– Photo by Mike Barr

Freethinkers were secularists. Some of them were atheists.

Many Freethinkers participated in the 1848 German Revolution. They fought against traditional European autocracy. When the revolution failed, a number of Freethinkers sought freedom and democracy in America.

About a thousand Freethinkers eventually settled in the Texas Hill Country in the communities of Comfort, Sisterdale, Luckenbach, Castell, Bettina, Cypress Mill and Tusculum (Boerne). Among the settlers were notable scientists, philosophers and engineers.

They came to the frontier with muskets, plows and axes but also with works of art, musical instruments and books.

Since many Freethinkers spoke and read Latin and considered fluency in that language essential to a cultured intellectual society, the settlements were known as Latin colonies.

In 1854, at a San Antonio Saengerfest organized by

Freethinkers, the group published a set of resolutions demanding, among other things, simple laws that anyone could understand, the abolition of capital punishment, taxation based on income level, the elimination of religious instruction in schools, the abolition of temperance laws, and the abolition of the grand jury.

Freethinkers were ahead of their time in many ways. They advocated equal rights for women. They opposed slavery and secession.

About half of the Hill Country Freethinkers gathered in Comfort. A group of Freethinkers met there for much of the 20th century.

At Bettina Colony in what would become Llano County, a group of idealistic young Germans from Heidelberg, Giessen and Darmstadt hoped to build a Utopian colony on the Texas frontier based on friendship, freedom and equality.

Bettina was the first communal society in Texas. It had no formal social structure and no government. The founders believed any kind of institutionalized leadership was a form of tyranny.

Forty miles south of Bettina, Nicholas Zink built a cabin in the pristine wilderness near Bosom Hills in Sister Creek Valley. Zink, a civil Engineer who surveyed New Braunfels, was an educated man with a large circle of sophisticated friends. A number of those friends followed Zink to a settlement in the middle of nowhere that came to be called Sisterdale.

Zink and his friends were not dirt farmers but urban, cosmopolitan Germans. They were a fascinating collection of writers, scientists, radicals, anarchists, Utopians and revolutionaries exiled from Germany following the failed 1848 Revolution.

For a time, Sisterdale was a sanctuary of style and sophistication on the wild Texas frontier. When Prince Paul of Wurttemberg, visited Sisterdale, he was astonished to find such refined culture at a wilderness outpost where he dodged marauding Comanches the day before.

The Freethinkers were not ideally equipped for frontier life, but the intensity and depth of their drawing room conversations, in multiple languages, rivaled any similar discussions in Paris, Berlin, Vienna or London.

The Freethinkers were Germany’s best – the most educated and enlightened people of their day.

And yet outside the Latin colonies, Freethinkers were a controversial and often despised minority. Even other Germans didn’t agree with them.

Their religious skepticism made people uncomfortable. Freethinkers became a target of scorn for more conventional thinking Texans.

Then the Civil War came, and the scorn turned to something more sinister. Suddenly the Freethinkers’ progressive ideas of liberalism, humanism and freedom and equality for all began to sound downright dangerous.

To most Texans, the Civil War had no middle ground. Anyone who opposed secession was the enemy. Any talk of abolition was treason.

After Texas seceded, Confederate authorities in Austin responded to the Unionist threat by ordering all citizens to take an oath to the Confederacy. The Freethinkers, along with many other German Unionists, were caught between a rock and a hard place.

As tensions escalated, German Unionists formed a militia called the Union Loyal League for self-protection. The state government in turn declared parts of the Hill Country in rebellion.

At about the same time the Confederate government in Austin organized a force of state militia and Confederate cavalry to patrol the Hill Country to put down what was perceived to be open insurrection by Hill Country Unionists. This force of Confederates, commanded by Captain James Duff, bivouacked near Fredericksburg.

– Photo by Mike Barr

On August 1, 1862 a group of German men, many of them Freethinkers, met on Turtle Creek, 18 miles west of Kerrville. Sixty-one of them decided to flee to Mexico. They planned to cross the Rio Grande at Del Rio, double back to Louisiana by boat and join the Union forces that had recently taken New Orleans.

The Confederates got wind of the plan, and rode in pursuit.

On August 10, 1862, mounted Confederate raiders, dispatched by Captain Duff, attacked the Germans encamped on the banks of the Nueces River. The Confederates killed 19 German Unionists and wounded 9 others. Confederates executed the wounded a few hours after the battle.

Of the Unionists who escaped, at least 8 more died trying to cross the Rio Grande into Mexico.

The Battle of the Nueces River was controversial. Confederates regarded the event as a military action against insurrectionists. Most Hill Country Germans considered it a massacre.

After the battle, friends and family members brought the remains of the dead Unionists back to Comfort for burial. The community erected a memorial at the burial site.

The Treue der Union monument 1866 on High Street in Comfort is the only German-language monument to the Union in the former Confederacy.

Meanwhile the disruption of society during the war broke up what was left of the Latin colonies. Some Freethinkers sought safety in more urban areas. Some went back to Germany. But a strain of Freethinking still runs through the German Hill Country however prickly that strain might sometimes be.

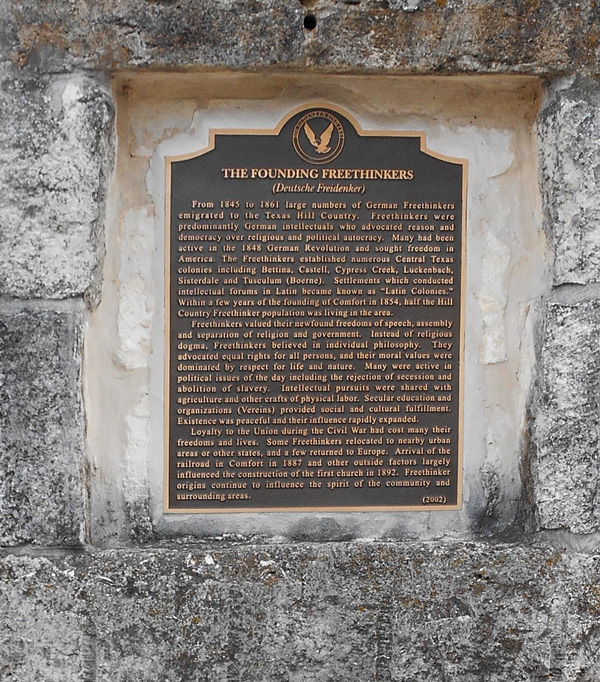

In 1998 a group of modern self-styled Freethinkers, with approval of the proper authorities, placed a 12 feet high, 32 ton limestone boulder in the public park along Texas Highway 27 in Comfort. The plan was to attach a plaque to the boulder as a monument to the Freethinkers who had played a significant role in the region’s history.

Then Comfort had second thoughts. The proposed language on the plaque was controversial. Some citizens were upset with what they saw as a memorial to atheists.

So community leaders shelved the project. Workers took down the boulder and a truck hauled it away.

It took 5 years to resolve the dispute and get the wording on the plaque just right. Today the down-sized monument to the Freethinkers is not in the park but on private property next to the Ingenhuett Building on Comfort’s High Street.

Modern day Comfort is not completely comfortable with the unconventional Freethinkers.

The Freethinkers, I suspect, are okay with that.