It happened just like in the movies or on TV. Four teenagers from St. Mary’s School formed a band. They played their first gig at the Girl Scout Cabin on Austin Street in Fredericksburg. Two years later they had a recording contract. It’s the kind of story that keeps the myth of the “overnight sensation” alive.

In 1964 Lyndon Johnson was president, the Vietnam War was escalating, women’s skirts were shorter, men’s hair was longer and the British music invasion hit America like Muhammed Ali hit Sonny Liston. Young people in big cities and small towns all over the country bought guitars and drums and turned garages into muffled practice rooms, hoping to duplicate the success of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. It didn’t matter that a typical 60s garage band had a better chance of being injured by a toilet than becoming rock stars. The guys from Fredericksburg were chasing a dream close to the heart of every kid who ordered a Silvertone guitar from the Sears catalog.

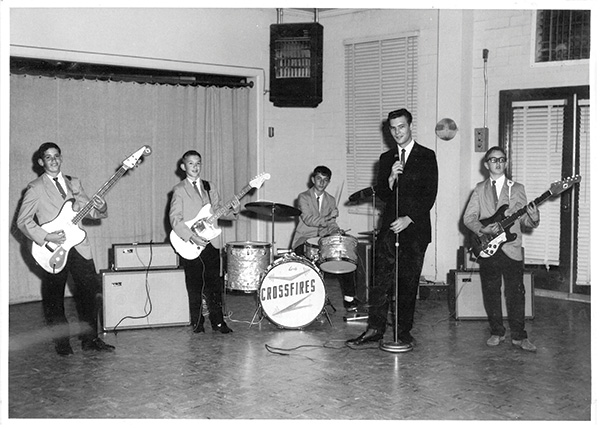

In March 1964, Gary Jenschke, Ken Molberg, Gary Itri and Jimmy Panza played together for the first time. Jenschke and Molberg had just finished the seventh grade at St. Mary’s School. Panza would be a freshman; Itri a sophomore. They called themselves The Fugitives, hoping that delinquent sounding name would offset their clean-cut choirboy image.

Johnny Almon, a DJ at KNAF Radio in Fredericksburg, joined the band as lead singer in 1965. When Johnny left, drummer Jimmy Panza took over as lead vocalist. The Fugitives, now called the Crossfires, performed at proms, fraternity parties and military bases. They played Pat’s Hall in Fredericksburg and the New Orleans Club in Austin. They shared the stage with the 13th Floor Elevators and Doug Sahm. They performed on Cactus Pryor’s TV Show on Channel 7 in Austin.

In the summer of 1965, The Crossfires entered the Battle of the Bands contest in Dallas. The group finished seventh out of 78 bands, but fans and music executives took notice. This band was going places. The following summer, with Jimmy Panza’s dad Bill as manager and mom Marge as chaperone, the Crossfires packed the trailer and headed west to the land of peace, love and rock and roll. Through contacts made in Dallas, they found work in Los Angeles. They played at PJ’s on Sunset Strip and the Troubadour Club in West Hollywood. They had to get special permission to play in some of the clubs. They weren’t old enough to get in. But age didn’t matter. These guys had talent. Success came at bionic speed. Three weeks after arriving in Los Angeles the band landed a record deal.

The man who recorded The Crossfires was Richard Podolor, better known as Richie Allen. In addition to producing The Crossfires, Richie produced Three Dog Night, Alice Cooper, Steppenwolf and Iron Butterfly. Within days of signing a contract The Crossfires were in the studio. Their first single was a song called “Who’ll Be The One,” released in the summer of 1966. Meanwhile in another part of Los Angeles, NBC television put out a casting call for actors to play rock stars in a TV sitcom. The show, called “The Monkees,” was inspired by the Beatles’ film “A Hard Day’s Night.” With the help of some excellent songwriters and backed by a room full of talented studio musicians, The Monkees would sell over 75 million records. After the Monkees hit it big, their record company beat the bushes for another young group to capitalize on the success of The Monkees. The Crossfires seemed the obvious choice.

“We signed with Colgems Records in 1967,” Ken Molberg remembered. “They changed our name to Fountain of Youth although none of us liked the new name very much.” The following spring Colgems (the name is a combination of Columbia Records and Screen Gems) released Fountain of Youth’s first single, “Livin’ Too Fast.” To promote the record, the company purchased a full page ad in the March 23, 1968 edition of Billboard Magazine. Suddenly the teenagers from Fredericksburg were running with some pretty fast company.

“The Monkees, Linda Ronstadt, Steppenwolf and Hoyt Axton were often in the studio,” Ken Molberg recalled. “In those days you never knew who might walk in. Mike Curb was in the studio a lot. So was Phil Spector. I remember talking to Barbara Eden. She was a singer as well as an actress. Let’s just say that talking to her was quite an experience for a 16 year old kid.”

The guys from Fredericksburg rubbed elbows and traded guitar licks with the legends of rock and roll. “We played on Steppenwolf’s first album,” Molberg said. “We did a show at the Hollywood Bowl with a lineup that included Jim Morrison and The Doors. We recorded a Carole King song called ‘Take A Giant Step.’ The Monkees recorded the same song as a B-side to ‘Last Train to Clarksville,’ but Carole liked ours better. Gary Jenschke played on George Harrison’s first solo album, and he did some studio work with the Rolling Stones. One day Hoyt Axton came in. He had written a song and wanted to do a demo. I played guitar on the demo. The song was ‘The Pusher,’ later recorded by Steppenwolf.”

Hanging out with music icons and TV stars was a thrill – for a while. But then the considerable pressures and frustrations of the music business set in. Record company executives wanted Fountain of Youth to play pop music that appealed to teenagers, but the band wanted to go in another direction. “The record company wanted us to be a boy band,” Molberg said, “but I wasn’t interested in being an imitation of the Monkees.

“I was interested in social issues and politics. There were serious things going on in the world. The music, at least the kind of music the record company wanted us to play, didn’t seem quite so important anymore. In 1968 we were practicing at Jimmy Panza’s house on Pecan Street in Fredericksburg when we heard Martin Luther King had been assassinated. A few months later Robert Kennedy died a mile from our place in California. That was enough for me. I went back to Texas.”

Gary Jenschke left the group a year later. He and Ken Molberg formed a band back in Fredericksburg. “We played together a couple of years,” Ken Molberg remembered. “Just fun stuff. Our last performance was in 1972 at the old dance hall in Luckenbach. Hondo Crouch, one of the owners of Luckenbach, was a friend of mine. I played on his mohair float in Boerne. After that show we called it quits. We were best of friends, but we went our separate ways.”

Molberg went to law school. Today he is a judge on the state court of appeals. Jenschke became a computer programmer. He died in 1993. Panza stayed in California to work in the music business. Today he lives in New Hampshire. And Itri spent his life as a musician and songwriter. He played bass for Roger Miller, and he wrote “Midnight Runaway” for Three Dog Night. He came back to Fredericksburg a few years before his death in 2014.

“The four of us had a great time,” Molberg recalled. “We enjoyed playing together. We never lost our love of music. But we had other things to do.”