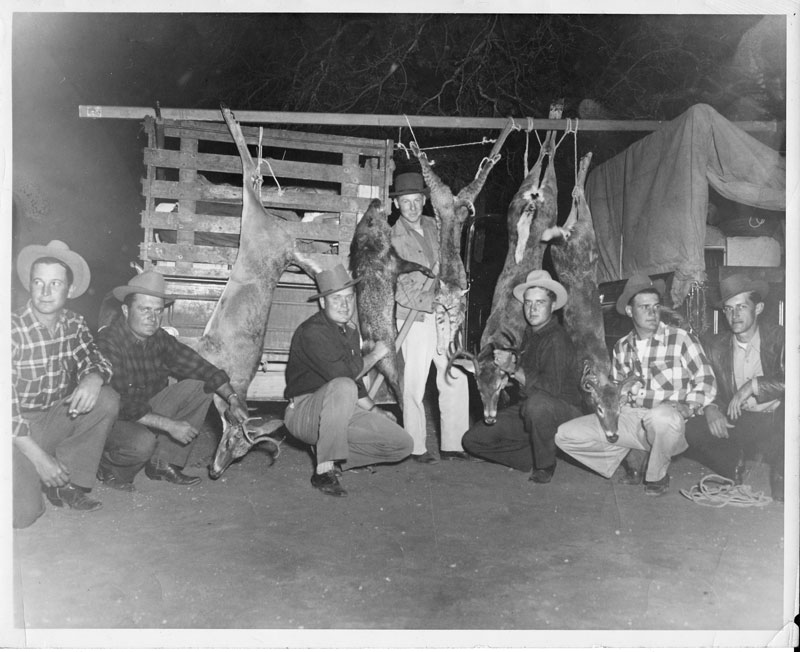

The story is similar: once a year, during or after deer season has ended, families around Central Texas gather, pool their whitetail harvests, and spend the day grinding, stuffing, tying, and smoking sausage. Some of these families trace roots back to the earliest wagons. For many, the annual tradition is as natural as the names Oma and Opa are familial. But I was born and raised in South Louisiana, an Ausländer to these hills, and the pervasiveness of this sausage-making heritage has piqued my interest – cultural foodways as nuanced as the Creole and Cajun cuisine of my hometown, maybe less celebrated, but perhaps more practical.

In the earliest local cookbook I could get my hands on – a 1916 edition of the Fredericksburg Home Kitchen Cook Book, put together by the Fredericksburg PTA – there are recipes for sausage: Blutwurst (blood sausage), Leberwurst (liver sausage), and Wurstrezepte (which simply translates to “sausage recipes”). Yet none of these recipes mention the use of venison and instead are written based on pork-centric, Old World sausage traditions. By the 8th edition, published in 1962, there are a few more venison recipes like “Dried Venison” and “Venison Ribs,” as well as “Sausage Surprise’’ which instructs the reader to “make small, thin patties of homemade sausage-meat” which then gets topped and baked with biscuit dough. Surprising still, there isn’t a recipe for the venison sausage itself.

The inclination to stuff chopped meat into a casing of sorts as a way to preserve the harvest and extend the season is at least as old as written language itself. There’s archeological evidence pointing to the fact that Summerians were making sausage around 6,000 years ago, and indigenous peoples inhabiting what is now Texas made a food called pemmican – dried meat (usually bison) mixed with tallow that was preserved either in the stomach, intestine, or a bag made of sewn hide called a parfleche. Perfectly preserved in fat, an anaerobic environment, meat stored like this could last for literal decades. The pemmican would harden, and then be sliced off in blocks and eaten cold or fried… not unlike German headcheese, scrapple or panhaus, as most in this area call it.

Unsurprisingly, I talked to several locals who remember storing their sausage stash in large crocks of lard kept in the smokehouse…er, haus. Before our industrialized food system, preserving meat was a matter of survival: store it in a way that inhibits spoilage and bad bacterial growth so you can have ready-to-go calories in leaner times. A bonus? Sausage is easily portable. When German settlers made their way to Central Texas, they brought with them all of their Old World butchery, meat curing, and wurst-making skills… and then made them Texan.

HISTORY

In the late nineteenth century, after the Civil War left the country crippled and native bison herds had been decimated, Texas had beef. The commercial meat market was born from these herds, and from community traditions of butchering and barbecue. During this time, sausage was transformed from a homemade food to a commercially available one. In Elgin, a man named William J. Moon made Texas sausage famous and established Texas’s first recorded barbeque restaurant, Southside Market. This specific style of sausage, affectionately referred to as “hot guts” is distinguished by its mostly-beef, coarsely-ground filling. By the 1880s, you could buy sausage in meat markets across the state, many of which were run by German, and then Czech immigrants – the latter of which are thought to have introduced garlic to sausage recipes.

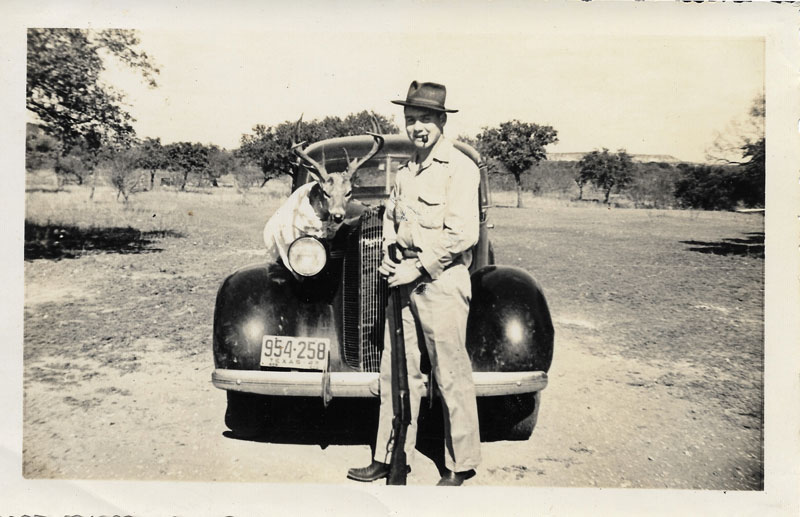

But Hill Country sausage isn’t famous. The recipes, truly, live in the homes and memories of those making it. My mother-in-law, Holly Schmidt, keeps her family sausage recipe written (in her mother’s perfect cursive) on an old index card that lives in a small card-sized red binder, which also holds records noting the size and weight of who shot what deer, what year. The last entry of the deer cards was 2001. My friend Megan Koennecke’s family keeps its recipe in an even more practical location: written in sharpie on the sturdy wooden table her great grandfather built, pulled out of the barn and used exclusively for wurst-making, once a year.

Dutchman’s Market told me they sell around 50 sets of natural hog casings a month, and each set can make around 100 links. Considering Dutchmans is only one of several spots selling casings, my very adrift calculations estimate there are tens of thousands of links of homemade sausage made annually, in Gillespie County alone.

WHAT WURST?

“We can say that food has nationality, but it used to be rooted in a landscape, in nature. That’s a much better way to talk about food.” – Chef Adán Medrano and author of Truly Texas Mexican: A Native Culinary Heritage In Recipes

After my failed attempt to find published venison sausage recipes and in an effort to more deeply understand this mysterious sausage culture of my new hometown, I called Bill Dumas, Texas’s own Sausage Sensei (pit master, sausage-maker, historian, and enthusiast). My questions were about provenance: what type of German sausage are all of these families making at home? Is it most like Bratwurst or maybe Knockwurst? Is the dried sausage just Landjäeger or Mettwurst? “I think this is something absolutely, uniquely Texan.” When the first Germans settled in Central Texas, they were greeted by a warmer and more humid climate. So they amped up the salt (and spice) content in their recipes to ward off bacteria. They also added smoke, another layer of protection. “They had to adjust everything that they knew,” Bill said.

I can’t help but shake the desire to stuff borders around this wurstmaking, but Bill, in all of his sage wisdom, paints an analogy using Bluegrass music. “When you go to Ireland and Scotland… you have the bands with the fiddle, maybe they have a banjo and maybe one of those little drums and they’re just doing their Irish or Scottish thing. And they’re playing their hearts out. But you hear elements that sound really familiar, right? In respect to chord structure and the way the songs themselves are put together.” Of course, bluegrass is the sum of all of its parts, with Scottish and Irish ancestors, but with influences from all over Appalachia that spanned several generations and picked up elements from blues and jazz. “And now the sausage is the exact same way,” said Bill. “Yes, it’s in a tube form. Yes, it’s made with pork and other secondary proteins and [then] seasoned. But that’s where the similarities end.” When families with generations of wurst-making traditions made a home in Central Texas, then covered in grasslands and savannahs, white tail deer roamed free. And without a neighborhood H-E-B, the land was the grocery store. Like champagne, a link of dried whitetail venison and pork sausage, stuffed in a pocket for a midday snack, is a true product of (Central Texas) origin.

BACKYARD SMOKEHOUSES

It seemed just about everyone I talked to with a German-sounding last name makes, or at least has made, venison sausage.

I’ve been slowly calibrating my gauge for German hospitality over the past two and half years of living in the Hill Country. To be sure, it’s different from the smack-you-in-the-face hospitality I’m used to in Cajun country; maybe a little harder-earned, though nonetheless sincere. Just to be safe, I turned to my old friend Megan and asked her to set up a meeting with her parents to talk sausage. Maybe an odd request, but they happily coddled my curiosity.

Mickey Koennecke, originally from near Fredericksburg, and Mark, from closer to Johnson City, met in high school when they were attending a rodeo dance at Burg’s Corner. They became official boyfriend-girlfriend at former dancehall mainstay Pat’s Hall, and they grumble in German idioms. They both grew up making sausage. “I know that I got in trouble going to school at Johnson City one time for taking sausage to school and selling it. But the principal was Merz, and he was a German guy. He understood where I was coming, so I didn’t get in a lot of trouble. I was just told to quell my enterprise,” Mark recalled with a teenage grin. “I’ve always wanted to teach my kids two things: to play 42 and make sausage.” That he did.

Each year the Koenneckes get together and turn their venison (plus pork) into sausage, each family member easily falling into their role that seems to have been ascribed at birth – some grinding, some stuffing, some tying links. The way they tell it, it’s very orderly, near restaurant-like efficiency, except the Koenneckes are making sausage in a backyard, and in the case of my in-laws – on a porch. And if you’re Leroy Esensee, another interview for this story, in a garage. Mark put it best, “See, every family does it a little different. It’s all good. But like, every family has their own little recipe. But none is bad. Just everybody’s a little different.”

Mark remembers when his family upgraded to an electric grinder. “We used to grind it by hand. And when we got an electric grinder, we thought we were uptown.” The Koenneckes still use Mark’s family grinder, and Mickey’s family tying technique which involves pre-cutting all of your string lengths (versus using one long string). After the sausage is tied, it’s hung in the smokehouse where it’s hit with a relatively cool smoke, usually of a hardwood like oak, for about 4 hours. Just about everyone I talked to followed this basic formula, and at this point, most folks take down some sausage to freeze as “cook sausage” (or fresh sausage), and the rest is left to dry for another week or two, weather depending, to make dry links. Mickey remembers butchering being a weekend affair that included the killing of a hog surrounded by huge black pots of rendering lard, and simmering blood that you’d have to constantly stir to avoid coagulation. Back then, her family went the extra mile and made delicacies like blood sausage, head cheese, and panhaus. Some families may still toil over vats of bubbling blood, but I think I’ll have to go to Sauer Beckman’s annual sausage demonstration to see these oldest of the Old World recipes.

I met Leroy Esensee, now going on 73, in his dining room. I could see the bottom loops of dried sausage he had hanging in his kitchen. He told me about the first time he ever made sausage. “We made 300 rings. Lord mercy, did I have a thought!” he told me with a drawn-out chuckle-sigh. “We sat there till 3 o’clock in the morning, cranking, that old hand crank stuffer, that matter of fact I have in that back room there. And after 300 rings of sausage, then [we] had to throw it out to the cows for a saltlick. It was so salty. I don’t know what I did. Read the scale wrong, or something. It was terrible. We finally got it to where you could eat it better.” Leroy’s earliest sausage memory was that of his postman sharing crocks of lard-preserved links with him and his siblings. “As a treat to us kids… he’d pull that little sausage out of that grease, wipe it off as good as you can, and start eating it, and by [the time you] finish you have all that stuff sticking to your mouth.” Sounds lip-smacking. Leroy sent me home with a link of dried sausage from his dwindling freezer stash which I carefully sliced up the next day for a photograph, and then a snack.

Sausage-making seems more tenable when you’re butchering the deer yourself, but with processing houses in every corner of the county, it can be tempting to go this route instead. I speak from personal experience. But these regional sausage traditions – born from Germaneness and preserved through ownership or access to land on which to hunt – could easily become a thing of regional folklore instead of… supper. Regan, my fiance, remembers when afterschool snacks were a piece of folded over “butter bread” with sliced, dried sausage. And Evelyn Weinheimer, who I met at the Gillespie County Historical Society archives, recalls sandwiches of fried blood sausage and molasses. It’s a small thing, these snack memories, but it’s also the sinew of a hyper-specific foodway fairytale.

As an Ausländer, all I can say is, I much prefer your version of sausage parities. Please keep it up. Case closed.