The groaning sounds and the flames dancing along the summit against the inky summer sky may have rational scientific explanations, but like the other myths and legends that surround Enchanted Rock, those mysteries are best left to the imagination.

Don’t try to make sense of it. Just relax, listen and enjoy the scenery.

The old Germans called Enchanted Rock “Zauberberg” – Magic Mountain, but the ghostly visions and the superstitions were part of the story long before the Germans showed up. It was the Native Americans who first called the rock “enchanted” or some comparable indigenous word.

A legendary frontier highway called the Pinta Trail guided wandering natives to Enchanted Rock. The Pinta Trail ran north from San Antonio to the hills above Boerne. It crossed the Guadalupe near Waring, entered Gillespie County near Bankersmith and wiggled through the pass at Cain City.

The trail forked after crossing the Pedernales south of Fredericksburg. One fork headed in the general direction of Mason, following what is today Highway 87. The other fork turned north following what is today Ranch Road 965. That fork looped around Bear Mountain, dropped into Crabapple Canyon and crossed Sandy Creek at the foot of Enchanted Rock.

Spiriting

In the Native American culture, spirits lived in rivers, springs, mountains and other natural objects, particularly grand or unusual places. Enchanted Rock, the most imposing natural wonder in the Hill Country, housed a multitude of restless, noisy guests.

Comanches, camped along Sandy Creek, heard moaning sounds coming from the rock in the evenings. They saw fiery apparitions in the moonlight, floating spirits of dead Indian princesses and ghosts of phantom warriors killed in battle.

A visitor to Enchanted Rock in the 1840s wrote: “At night a bright light is supposed to be seen issuing from the top. The Indians had a tradition that the fires in former years had come from the crevices and they imagined that the rock was at one time the abode of an Indian deity. They formerly had rude structures on the summit where they offered sacrifices to the Great Spirit.”

By the 19th century an increasing number of Spanish soldiers, missionaries and treasure hunters came in contact with Native Americans along the Pinta Trail. The attitude of the Spanish toward the natives was sometimes fatherly and sometimes hostile. The legends that grew from that complicated relationship added another layer of superstition and fantasy.

According to Spanish legend a soldier named Don Jesus Navarro fell for Rosa, an Indian maiden who lived at Mission San Jose. The Comaches attacked the mission, captured Rosa and took her to be sacrificed to the spirits at Enchanted Rock. Then, just when it looked like Rosa was toast, Don Jesus saved her. Chalk up another fable for Enchanted Rock.

Adding to legend

Legends express characteristics valued by a particular civilization. Take for example the story of Texas Ranger Jack Hays, cut off from the rest of his men, single-handedly fighting off a Comanche war party from the top of Enchanted Rock. Whether or not the story happened exactly that way is for historians to debate. Either way it is a part of the legend.

For years Enchanted Rock, like El Dorado, was an elusive, mythical place. Settlers east of the Colorado heard stories about it but questioned its existence. Then eyewitness accounts made it real while adding to the mystery.

W. B. Dewees writing from “Colorado River, Texas, October 31, 1834” told of exploring “a large rock of metal which has for many years been considered a wonder.”

In 1838 a prospector returning from the San Saba with his hair still attached told of “an Enchanted or Holy Mountain” in the granite hills west of the Colorado.

In October 1842, Gen. Edward Burleson and his party, traveling north on the Pinta Trail, were awestruck by the sight of Enchanted Rock. A member of the party wrote, “The feelings and imaginations swell almost to breathless astonishment on beholding one immense solid rock of a dark reddish color.”

Each year mounting pressure from rangers, soldiers and settlers pushed nomadic Native Americans farther west. The Natives didn’t go quietly but were forced to give way to an aggressive culture of private ownership.

In 1838, the Republic of Texas awarded a land certificate to Anavato Martinez and his wife Maria Jesusa Trevino de Martinez. The certificate was payment for services during the war with Mexico. The block of land it represented included Enchanted Rock.

Anavato and Maria Jesusa sold their certificate to James Robinson in 1841. Robinson, former Lieutenant Governor of the Texas Republic, sold it to his business partner Samuel Maverick of San Antonio in 1844. Maverick hoped to find gold at Enchanted Rock but didn’t find much.

Maverick’s widow sold the property to N.P.P. Browne who sold it to rancher John R. Moss. Enchanted Rock would have 13 owners in all.

Meanwhile the Natives lost their grip on Magic Mountain. Needing a tangible object to blame they focused on the surveyor’s compass. The natives, who had no concept of owning land, saw in the compass an evil instrument a white man used to claim land to the exclusion to all others.

Attraction

But even a culture that celebrated private ownership sensed the spiritual and communal nature of Enchanted Rock. In the late 19th century, Rev. Dan Moore from Willow City held church service once a year on top of the rock. Worshippers walked to the summit or rode their horses. When they got there, they found out what Native Americans had known for centuries – that standing on top of Enchanted Rock one felt a little closer to heaven.

In 1927, Tate Moss, who inherited the property, opened Enchanted Rock to campers and hikers. Then in 1946, he sold the property to Albert Faltin, who continued to operate the rock as a private park. Later Faltin sold an undivided half-interest in Enchanted Rock to Llano rancher Charles Moss.

For much of its history Enchanted Rock was not easily accessible. It was far from populated areas and hard to reach.

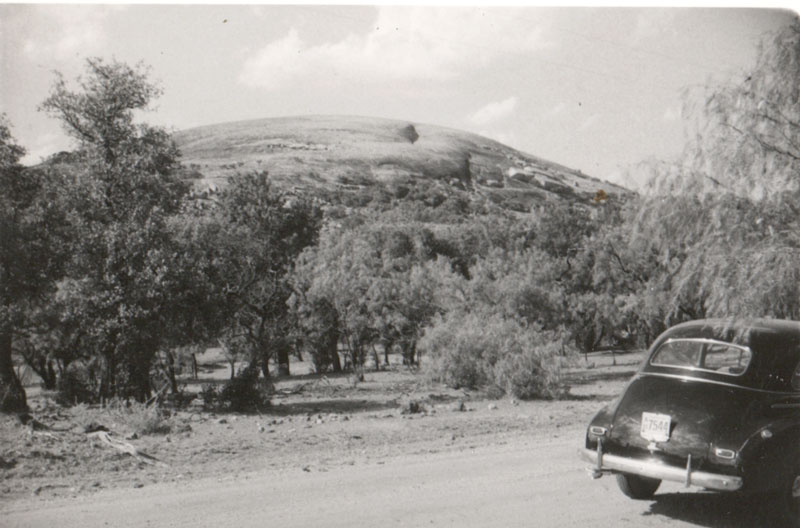

Then in the 1950s, the world discovered Enchanted Rock. Paved roads and concrete bridges made travel easier. Nature lovers came from all over the country to climb the rock’s gentle slopes.

Along the way something amazing happened. Enchanted Rock proved to be the perfect antidote for the unfortunate side-effects of an increasingly urban society. The rock was the ideal place to go when the world closed in. Just being there calmed the jitters, cured the blues and eased a troubled soul.

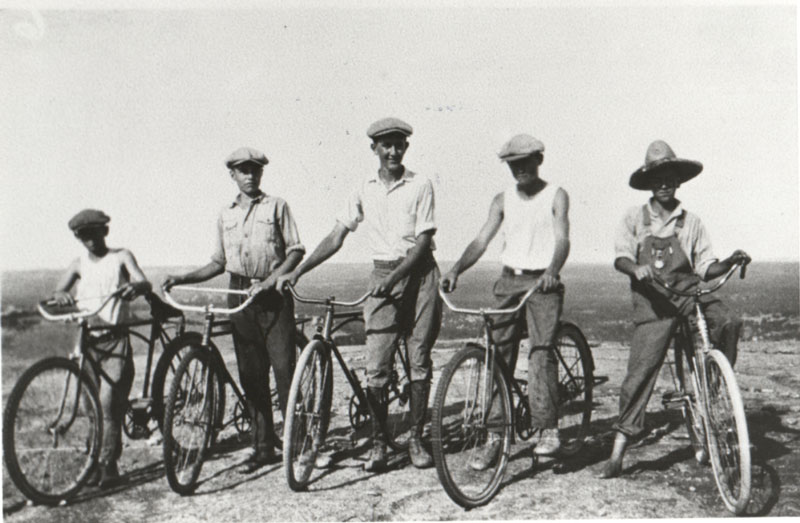

At the same time, Hill Country families knew they had one of nature’s wonders right in their own back yard. They celebrated birthdays, holidays and other special occasions with a picnic along Sandy Creek. Then they would climb Enchanted Rock in their Sunday clothes and pose for pictures on the summit.

Still other climbers found unconventional ways to the top. A Boy Scout troupe scaled the rock on bicycles. A GMC pickup from Behrend Garage in Fredericksburg conquered Enchanted Rock as a publicity stunt.

Spirit’s park

In 1955, the National Parks Service considered making Enchanted Rock a National Park. That same year Lincoln Borglum, son of Mount Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum, visited Enchanted Rock, floating the idea of carving the faces of famous Texans into the side of the mountain. Fortunately that proposal never got off the ground.

By the 1960s, momentum was building for Enchanted Rock to become a state park. The owners, like the Native Americans before them, knew the Magic Mountain was too grand and too important to belong to a person or even a family.

Enchanted Rock was special. It belonged to the spirits.

In the 1970s, the Moss and Faltin families offered Enchanted Rock to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department for $1.3 million. At first, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department couldn’t meet the asking price, so the Nature Conservancy, a private conservation group from Virginia, bought the property and acted as interim owner until the state could assume ownership in 1978.

“People climb Enchanted Rock to find solitude,” said Doug Cochran, Superintendent of Enchanted Rock State Natural Area. “At the summit you can relax. It’s peaceful. You can hear the birds and feel the breeze. The view from up there is spectacular. You’re surrounded by nature. There’s nothing else like it.”

To protect the view, The Parks and Wildlife Department has long-term agreements with surrounding landowners. The agreements, called conservation easements, give landowners tax breaks in exchange for limiting development on their property.

As Supt. Cochran explains, “We want the view in 2051 to be the same as it is in 2021.”

Keeping things natural is a standing order at Enchanted Rock. There are campgrounds and some crude paths to facilitate hikers. Otherwise, the rock, with its trickling springs, prickly desert foliage, delicate flowers, spirits, myths and legends, is just as the Comanches left it.

So enjoy the view. Leave the rest to your imagination.

Recommended Reading: Enchanted Rock: A Natural and Human History by Lance Allred