Texans care about preserving natural resources. We treasure the land, the wildlife, and especially the water. But too often we ignore what’s right over our heads: the night sky.

Britton Waldron, Gillespie County resident and night sky-advocate, likes to ask urban-dwellers this question: “Do you like seeing the Milky Way?”

“A lot say, ‘I’ve never seen it.’ Most people haven’t,” he said. “Once you see it, it’s just absolutely majestic.”

Estimates are that 80% of Americans have never seen the Milky Way, due to light pollution. The good news is it’s the easiest type of pollution to fix .

“We can eliminate light pollution, I like to say, at the speed of light, by switching a light off,” said Dawn Davies, night sky program coordinator at Hill Country Alliance, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the region’s natural resources.

For the lights that do need to stay on, it’s about smarter lighting — lighting the ground rather than the sky, using bulbs that glow with warm-toned light in the proper temperature range (see sidebar). Use of motion sensors and timers also cuts down on light pollution. Night sky-friendly lighting is, in the long run, cheaper. Save pennies, save the stars.

Davies says one of the dangers of traditional lighting is glare, and glare makes us unsafe.

“People believe the more light you have, the safer you are. The truth is the better night sky-friendly lighting, the safer you are. What happens is people use so much light they create glare, and glare can disguise unsafe situations. Lighting being properly directed means less slips and trips and less workplace injury,” she said. “It’s not turning out all lights, but learning how to use right lighting, shielding it and directing it where it needs to be, facing down or on an area designed to be illuminated instead of tossing it out into the night sky.”

Communities and parks can apply to be certified as Dark Sky Places by the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA). In the Hill Country, Dripping Springs, Fredericksburg, Horseshoe Bay and Wimberly Valley have all been designated Dark Sky Communities. Dark Sky Parks include Enchanted Rock State Natural Area and South Llano River State Park, both of which offer educational events, like star parties. Davies hopes to get every state park in the Hill Country IDA certified and to get parks near major cities to use night sky-friendly lighting, to better show off the stars.

Astro-tourism in the area will get a boost on April 8, 2024, when the arc of the total solar eclipse passes through Kerr, Gillespie and Llano counties. Even though that event happens during the day, it will bring attention to the sky. Those big, bright Hill Country nights are already one of reasons people visit the region — because deep down, we know we need to look up.

“It’s really primordial, at the root of who we are as human beings,” Davies said. “We can bring that back, preserve pure night skies and do something for the soul as well.”

Darkness is an essential aspect of life. Some birds migrate at night. Lightning bugs need night in order to mate. And the American Medical Association reports that prolonged exposure to harsh light reduces the body’s ability to produce melatonin, which may increase development of certain cancers and interfere with sleep health.

So how do we spread the word about preserving clear night skies? Wayne Gosnell, president of Blanco County Friends of the Night Sky, says his community uses a multipronged approach. The group has sponsored contests for essays, songs, and art and photography that celebrates the night. Blanco Friends recognizes businesses, neighborhoods and home developers that use night sky-friendly lighting. Gosnell would like to implement a program to recognize wineries along Highway 290.

“We think it would be in their own economic best interest, especially for those wineries that offer accommodations,” he said. “Do the wine trail, come back at night, enjoy another glass of our wine and enjoy the night sky.”

But wineries will need the cooperation of their landowner neighbors. Gosnell created a downloadable flyer titled, “Hold On, Pardner. That’s Trepassin’!” which explains in a humorous way how to approach a neighbor whose outdoor lighting creeps past the property line. Because even Blanco, a town of only 2,000, emits light that can be seen from space.

Looking skyward

One person who spends as much time as possible looking into space is Kenric Kattner. His day job is corporate restructuring, as a partner at Haynes Boone. His night job is watching the stars through his telescope at Putman Mountain Observatory. From 2017-2020, Kattner served on the board of the IDA and was president for two years.

Both Ken and his wife, Laurie, grew up in big cities, and both developed an early love for the stars. In Houston, Laurie and her father would study constellations. In Dallas, Ken looked through a telescope at St. Mark’s School with a teacher named Mr. Dexter. On Ken and Laurie’s first date (a blind date), dinner was followed with time looking at the night sky.

As Kattner got busy with his career, he forgot about the view overhead for a while, until he picked up a copy of Sky and Telescope magazine at an airport. After a visit to McDonald Observatory in Fort Davis, he and Laurie talked about finding a piece of property in an area with enough night sky to take astrophotos.

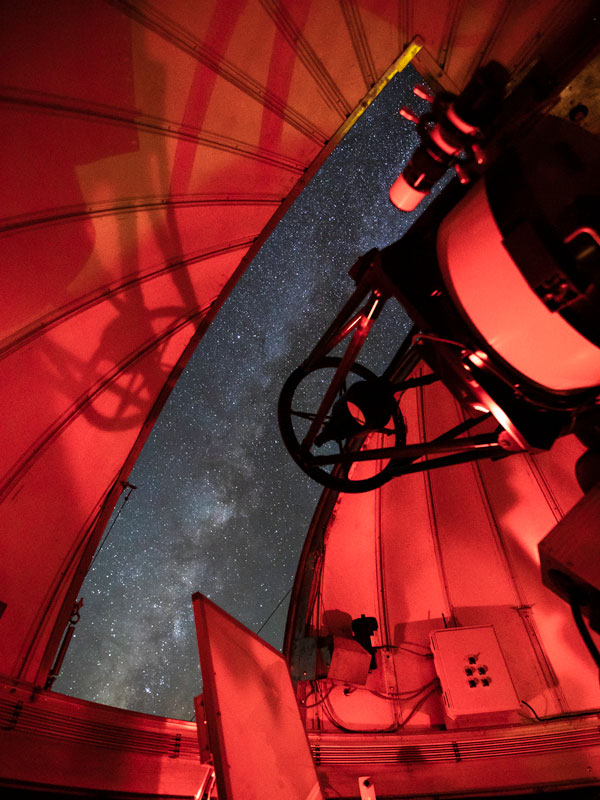

“We drove around maybe a thousand miles in the Hill Country, looking for a place that was dark,” Kattner said. They found 170 acres in southern Llano County, and with the expertise of architect Eric Mustard, constructed an observatory to house a telescope.

Since Kattner works in Houston and New York City, the observatory can be operated remotely. But as often as he can, he’s at the ranch, “on the edge of night.” The telescope is hooked up to computers that allow him to take pictures of what is beyond our vision.

“Before it gets dark, I decide what object I want to take a picture of,” he said. “You’ve got planets — they’re close. Then the stars in our Milky Way. Then outside that there’s really deep-sky stuff.”

It may take a few nights for Kattner to get the necessary footage. Once the data is collected, he mixes the information, stacking lumens and red, green and blue wavelengths to get the desired product, not unlike the way a sound mixer fiddles with tracks to make the perfect song.

Kattner also has sky quality monitoring equipment, measuring the amount of light pollution each night, every 15 minutes, unless weather prohibits accurate measurements. Information from Putman Observatory, as well as from Enchanted Rock, South Llano River, Lost Maples State Natural Area and Lady Bird Golf Course on the edge of Fredericksburg are all available at putmanmountainobservatory.com.

Preserving a dark haven

Kattner’s current passion is establishing a Dark Sky Reserve for a swath of land encompassing 550 square miles. Picture a triangle made by connecting the cities of Mason, Llano and Fredericksburg; right in the center is Enchanted Rock.

There is great interest in making that area’s skies as dark as possible. Central Texas Electric Co-op has adopted a resolution supporting Dark Sky initiatives, and this summer Texas Senate Bill 1090 made it easier for cities to receive IDA-accreditation. For the reserve to gain approval, both Llano and Mason will need to join Fredericksburg by becoming Dark Sky Communities. But that won’t quite be enough.

The trick is that in Texas counties can’t pass ordinances, such as lighting ordinances — only cities can. Much of the land in the proposed reserve is rural and privately owned, so buy-in will be a grassroots effort.

“I’m not sure if there’s any better way than to talk to your neighbor over the fence,” Kattner said.

Part of our heritage

That includes everyone from ranchers who can remember the dark skies of decades past to high-schoolers who may have never seen one. Kattner says the night sky is our “shared heritage.”

“Heritage means something we all own,” he said. “Humans live on the Earth, and we have the sky to look at. It’s worthy of being protected. If it’s not, we don’t have that commonality. We lose not just the connection of the beauty of the universe, but with one another.”

Kattner says some nights are so clear that he and Laurie don’t even need a telescope.

“We sit on the porch in the summertime, and we can hear the frogs croaking by the pond. It’s so dark we can look on the pond and see the Milky Way reflected in the water,” he said.

During my visit to Putman Observatory, we turned out the lights for a couple of minutes so the photographer could take night sky photos. I was sitting directly across from the Kattners at their kitchen table, and I couldn’t see them.

A few minutes later we stepped out onto the front porch, where the night sky-friendly lighting glowed a warm amber, only illuminating the steps down to the driveway. All around us were clear night skies. And there — above the pond — shone the Milky Way.