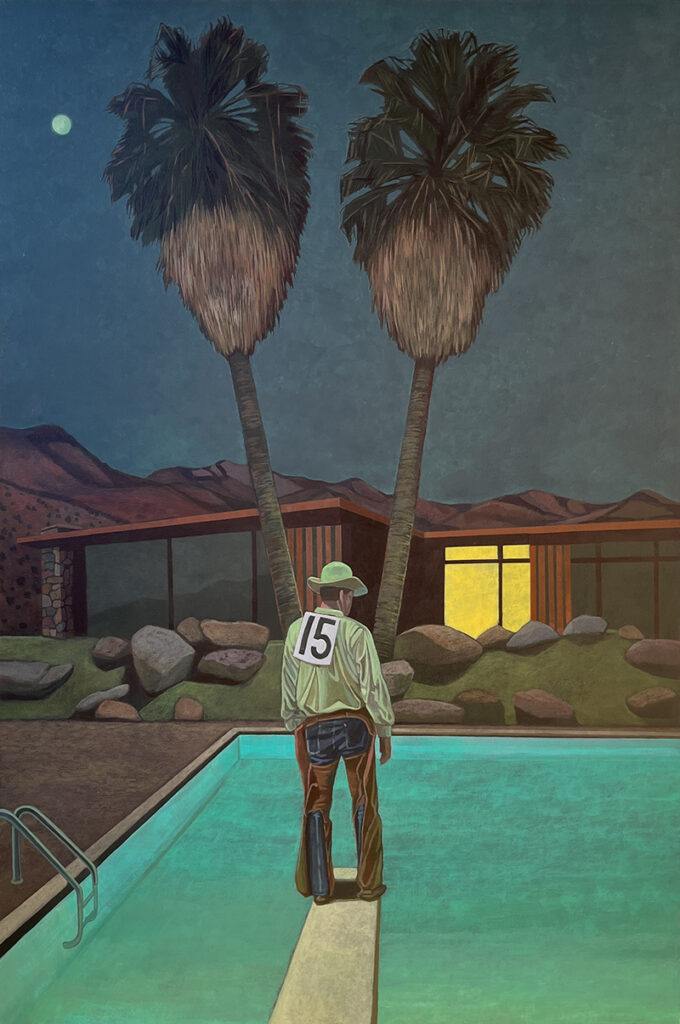

It’s a full moon, and the Palm Springs swimming pool is lit up with hues gradating from Caribbean turquoise to a shade of light sherbert, not unlike the frothy color of a 1950’s Christmas punch. The background is a dusky scene, featuring a retro ranch house, a darkened desert mountain range, and two towering palm trees, seemingly old and with a thick beard of dead leaves hanging beneath the gray-green ones. In the center of the foreground leading into the pool is a diving board, and standing at its edge, we see the back of a rodeo cowboy, still sporting his number 15 tag, riding chaps, and a felt hat. He’s staring into the pool’s crystal depths, maybe contemplating a plunge, a recent performance, or a western romance.

Really, we can’t know what the cowboy at the edge of the diving board is thinking, and according to the painter Kevin Chupik, who brought the scene to life, the why isn’t as important as the what. It’s a provocate painting that makes you look and wonder. “I tend not to dwell upon all the baggage that the fine art gallery people try to saddle me with. Pun intended,” he chuckles.

Chupik was born in Fort Worth, but in 1977 when he was 9 years old, he moved to Tuscon with his family. Their house was on the edge of town, and young Kevin could walk from his neighborhood home to the threshold of the Sonoran Desert, the wild setting for his indoctrination to the southwestern aesthetic. Surrounded by saguaros, he’d bring his BB gun to hunt rabbits and small fowl, drying the hides and cataloging the feathers in Ziplock bags.

At least once every other week, the family would visit a nearby dude ranch where the naturalist painter Ray Harm just so happened to be working, a subtle but formative introduction to fine art.

Chupik embraced his playground easily and wholly. Those years, “gave me a real mature understanding of what it was to be alone out in the wild. And I was. My sister and I never had a babysitter. We were unattended all day long. That’s kind of where everything started.”

Chupik got a Bachelor of Fine Arts from Texas Christian University. (This is also where he met his wife Andrea, who was studying graphic design.) While in college, he went on a school-sponsored trip to Santa Fe where he and other TCU students stayed at Georgia O’Keeffe’s ghost ranch. At the time, the trip felt no more than a collegiate romp, but in hindsight, Chupik sees it as something else: “It was really pivotal to the kind of work I was making — work that was very much about the West and landscape. I was trying to marry it to sculptural forms. The trip was really a kind of continuation of the aesthetic that Tuscon put into my soul.”

After graduation, Kevin and Andrea moved to Boulder so he could pursue an MFA, a seeming footnote to the easy access Colorado granted him to the mountains and high desert where the real adventure happened. “That’s really when my fiendish approach to the outdoors started,” he said. “I logged 16 [mountain biking] trips one year to southeastern Utah, Four Corners area.”

After Boulder, the couple moved to Las Vegas, deeper in the desert and surrounded by a landscape whose archaeology and ecology enchanted him. “At that time, it was my favorite place on earth.”

A month and a half after landing in Vegas, Kevin had a serious mountain bike accident that left him in a wheelchair. Decades later, he easily articulates the choice he was presented with, “I either have to reinvent myself or be miserable. And I chose to reinvent myself and I focused more on contemporary work.”

A lot of life has happened since the accident. Kevin and Andrea have built careers and had a daughter, Ava. They also moved back to Texas, eventually settling south of Fort Worth near Kevin’s family. All the while, Kevin has been painting, developing a style that is recognizable for its unique themes and alluring juxtaposition of the old west in a new form.

The walls of Kevin’s studio room are lined with vintage Western novelties like colorful plastic figurines and Rin Tin Tin memorabilia. It’s clear that he’s an enthusiast of nostalgia, able to pluck character or pantone inspiration from vintage Western motifs. “I’ve always been a collector of images. I am grabbing an image and tucking it away. I’ve got thousands of them. I keep some on the back burner.”

And some get brought to the forefront, combined in a way that’s interesting and suddenly alluring. Using software like Procreate, Kevin can understand what works well together before putting brush to board. “Whatever I need to do to create that vision that I have in my head, that concept… whether it’s drawing, painting or sculpture, painting or assemblage, whatever it is. The image is important to me.”

Chupik works in acrylic, a medium that helps him move fast, like a barrel racer rounding the bend.

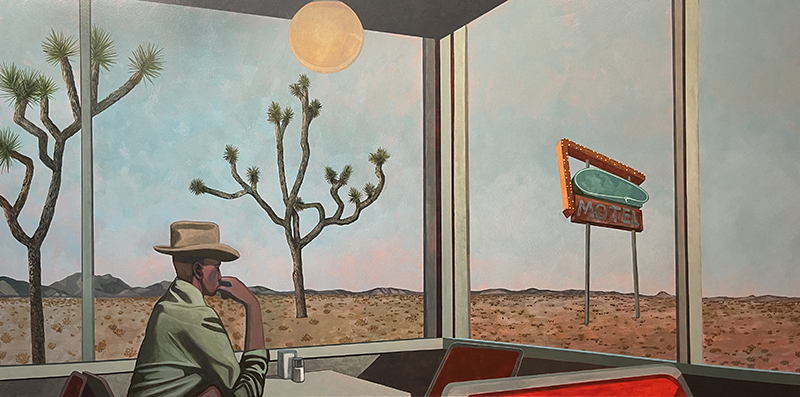

“I think a lot of my inspiration comes from my longtime favorite artists, or one of them, René Magritte,” best known for his surrealist images of clouds, bowler hats, and green apples. “When you get that moment where there’s a little bit of suspended disbelief, that what you’re looking at isn’t, in fact, real or possible,” he said.

Referring to one of his more popular paintings of a lone bison standing in an empty convenience store parking lot and staring at an ice machine, Chupik says, “I think the main thing I tried to do is make things that might be improbable possible.” Certainly, there could be a world where a mammoth bison gazes upon a glowing ice machine, but would there be?

Many of Kevin’s characters — mostly cowboys and at least one buffalo — have a faraway feel to them, but their placement in a classically vintage mid-century modern aesthetic makes them as familiar as your childhood lunchbox. For this reason, Chupik’s art is approachable and likable. He recently hit the Instagram algorithmic jackpot, gaining several thousand new fans in a short amount of time, and nudging him into the category of “micro-influencer,” a distinction of which Kevin’s deeply skeptical. For better or worse, the social media platform is helping him sell paintings directly to collectors, skipping the gallery step altogether.

Like a good movie, viewing a good painting can transport you. But how about the act of creating one? “It’s my passport to access,” Chupik says. “And it’s kind of liberating in that way. I’m not restrained from any corner of the West in that regard, whether it’s Eastern Oregon or Southern Colorado or, you know, rolling hills on Montana. It’s a time period that goes between the mid-1800s all the way up to our present time. And in the way that Photoshop and Procreate work, I can place myself contextually in that area, I think largely because I know those tactile responses [of the West], the feelings. I know what it’s like — the crunch of the ground, the smell of the air, all those things. The nostalgia is so visceral to me. It’s probably the thing that keeps me going back. Really the desire to try and transport people along with me, like ‘come along!’ It’s more like I’m a tour guide in that way, and I’m sharing what I find to be very important.”

To see his work, head to his website kevinchupik.com

or follow along on Instagram @kevinchupik.