The only thing more colorful and layered than artist Dolan Geiman’s large-scale paper collages is the story of his life. Geiman grew up in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, where he was immersed in the raw beauty and unbridled freedom of the natural world.

Together with his sister, he remembers searching for treasure and finding inspiration in the many dilapidated farmsteads that covered the countryside. Those abandoned dwellings triggered an early fascination with old newspapers and lost love letters, worn books and peeling wallpapers that lingers to this day. Furthermore, a centuries-old tree across the creek from his home gave him a quiet place to blend in and observe the world around him. “I would climb as high as I could and find a little spot, and just sit and observe a hawk land, or a rabbit jump into a hole,” he says. “I was creating tales about what these creatures’ lives were like.”

Geiman’s mother was influential as well, constantly teaching him and his two siblings to treat Mother Nature with compassion and care. Once, he remembers being reprimanded after kicking over a large rock while out on a walk. That rock, she said, was not an ordinary stone, but rather, the roof off the home of a family of ants. “My mom really worked with us to have an awareness about our surroundings,” he shares. “She made it fun, but she was also trying to say that everything we do has an impact, and that really stuck with me.”

Today, Geiman’s contemporary western paper collages and striking metal sculptures are the result of a dogged and inspirational journey rife with resilience, persistence, and passion. As a teenager, the artist was withdrawn and admittedly uninterested in school, saying, “I wanted nothing to do with anyone’s ideas other than my own.” In fact, he wished to forgo college altogether, though it was his mother’s encouragement and ultimate offer to pay for his education that changed his mind. “My folks didn’t have a ton of money,” he says. “If this person who’s been working tirelessly for years to build her own career is now willing to take all the money she was saving and hand that to me, I better pay attention.”

Shortly thereafter, he enrolled in the entry level art program at James Madison University. “I got to art school and all of my peers were way better artists than I was – it really cracked my brain open,” he remembers. “It challenged me and made me want to wake up, start applying my skills, and try to understand how I could get better as an artist.”

Geiman’s time at JMU lit a pilot light in him, and he began to pursue various projects, from screen-printing T-shirts to painting and collaging, while raiding dumpsters for art supplies. Some of his favorite finds were old, discarded books, the covers of which he would rip off to create makeshift canvases for his work.

Through his late teens and early twenties, Geiman worked feverishly on his art, juggling jobs and often staying awake for days at a time in order to complete new pieces. After 9/11, however, he took a break and went to live with a friend in the woods of southern Virginia. “He saved my life, because he really got me out of trying to force this career on myself,” he says of his friend. In the end, that hiatus was the reset he needed to jump back into the work with renewed enthusiasm and vigor.

Over the next few years, Geiman moved in and out of various abandoned buildings near Charlottesville as he strived to support himself and develop his craft. Along the way, he met two fellow artists living on the street. Together, they began approaching different gallery owners in town. “We basically started harassing the owners to give us a show,” he says. “We just really wanted to be recognized.” Hard work eventually paid off for the trio who experienced repeated sold-out shows.

Geiman’s big break, however, came a bit later after reconnecting with his uncle who was passing through town. At the time, Geiman was living in an abandoned office building with his fellow artists, and he remembers feeling embarrassed when his uncle came by. “He’s always been a very upscale, successful businessman,” says the artist. “This is a guy who traveled all over the world, worked for big corporations, and has an amazing art collection.” In the end, his uncle not only liked what he saw, but also purchased some of his nephew’s pieces, and offered to host a show for him back home in Chicago.

That gesture of kindness and generosity marked a turning point in the young artist’s life. Following the show’s success, Geiman relocated to the Windy City to pursue his craft full-time. “That was the introduction to the rest of my career because as soon as I got to Chicago, I met my wife, Ali Marie, who helped me set up the business,” he shares. “From the beginning, it has been about hustling for me – that is all I know how to do.”

Work ethic aside, it is Geiman’s distinctive “folk-meets-urban” aesthetic and his use of salvaged materials, that has made him a nationally recognized mixed media artist. His art is fueled by an unrelenting resourcefulness learned over a lifetime of foraging and finding his way.

“When I was getting started, I couldn’t afford to go to an art store and buy paints so I would go by job sites and dig through dumpsters to see what was leftover in the paint cans they had thrown out,” he explains. “Everything I am working with is a material that has been discarded, and I get to give it new life.”

Many of Geiman’s discoveries, be it a torn ticket stub, a bottle label or receipt, have revealed themselves on long walks. After returning home, he looks through the detritus and ephemera collected, and pins select pieces onto his studio wall. Ultimately, it is a gratifying practice, and one that the artist encourages his fans to partake in too, saying, “That little thing that just blew in front of you might be more interesting than you think it is.”

The artist also enjoys taking road trips and stopping intermittently at junk yards or abandoned dwellings along the way. In the depths of his imagination, the patinaed pages of an old encyclopedia could become a flight of crows in the skies of his collage, while the clunky knobs from a trashed TV might make the perfect shoulder joint for a sculpted rabbit. “My brain almost has this post-apocalyptic vibe to it, where I’m like, ‘What can I save to use in my new world?’” he explains.

Regardless of what he is creating, the artist’s portfolio is always rich with narrative and storytelling. Recently, Geiman found an old eyeglass case filled with pen nibs in an abandoned home in Texas. “Putting my hands on these items that someone has loved and carried with them, there is energy in that for me,” he shares. “When I look at this case, I can see the worn part where someone’s thumb pushed it open for years, and those things have a story; I get to take that and use that story to build more story.”

In this way, Geiman’s work is often characterized as nostalgic in nature. “I have heard people who criticize it, because they say nostalgia is not a place that you should start from with art,” he says, “but I have always believed that nostalgia is one of the most honest feelings we can have.”

Given that most of his collages contain hundreds if not thousands of individual paper fragments, keeping the collections organized is a feat in and of itself. “When I get into my space, everything has to be tidy and clean because I get frustrated when I can’t find stuff,” he says. In the collage studio, a medley of tables and flat counter spaces offset the drawers upon drawers filled with paper organized by age and color. In every direction, the tools of his trade reveal themselves in the form of glues and paints, rulers and knives, pencils and pens, brushes and scissors. “When I am doing more detailed work, that’s when it starts to look like an operating room because I’ll bring out my fine and extra fine point scissors to make little, tiny cuts.”

Every one of Geiman’s collaged works begins with a sketch. As he ponders what the sketch will become, he starts compiling pieces, thoughtfully considering the subjects, colors, and corresponding materials that will make the story come alive. “Let’s say I have a sketch of a deer in the woods, and there is a cabin in the background. When I look at that sketch, I think, indigo background, pink deer, chartreuse rocks,” he explains. The artist has an uncanny ability to remember every item he has found over his years of collecting. “I can’t remember the person’s name at the grocery store, but I can remember that weird stamp I found twenty-five years ago.” When he is ready to assemble the collage, he works on thin wooden panels, drawing the design and then cutting and layering the papers, one-by-one. Many times, he creates his backgrounds out of salvaged music or hymnal pages, which has become one of his signatures over the years.

Music, as it turns out, is a constant in the artist’s studio, and ranges based on the mood and time of day. “If someone looked at the music I play from day to day, they would say, who are you? What is happening right now?” Is this Himalayan or Mary Poppins,” he laughs adding, “I think for me, my brain works like that.”

Today, Geiman’s subject matter is a celebration of the rugged American West, be it flora, fauna, and wildlife, or powerful human characters with stories to tell. Some of his most renowned subjects are his vaqueras, or Southwestern cowgirls, with their faces painted like the Day of the Dead. The collection was inspired by the strong women in the artist’s life and his desire to create a new type of Southwestern folk mythology. “I felt like every time I heard a story about the Wild West, it had men like Wyatt Earp, yet there were all these women that never get talked about,” he shares. “I wanted to create my own line of characters that came up from Mexico, and then decided to take over and do really awesome, amazing things as women in the West.” Since launching the series, it has resonated widely with fans, and continues to be one of the most popular collections in his extensive portfolio.

Though much has changed since Geiman’s early days spent scrounging for supplies, the artist’s hustling spirit never wavered. Today, he works prolifically, often starting anywhere from six to eight pieces at a time with countless hours spent hand-cutting every piece of rescued paper. In addition to his renowned paper collages and metal wall sculptures, he also pursues projects in screen-printing, painting, and woodworking, to name a few. Furthermore, Geiman sells his work online and in more than one-hundred-thirty different stores across the United States, one of which includes Blackchalk Home and Laundry in Fredericksburg.

Blackchalk’s owner, Jill Elliott, is one of Geiman’s earliest supporters. “She is probably in the top three stores because she understands and appreciates the work,” he says. Jill was also one of the first accounts to carry his coveted original art, a right reserved to just five stores today. “She is able to narrate what is happening to her clients and help them understand what the pieces are.”

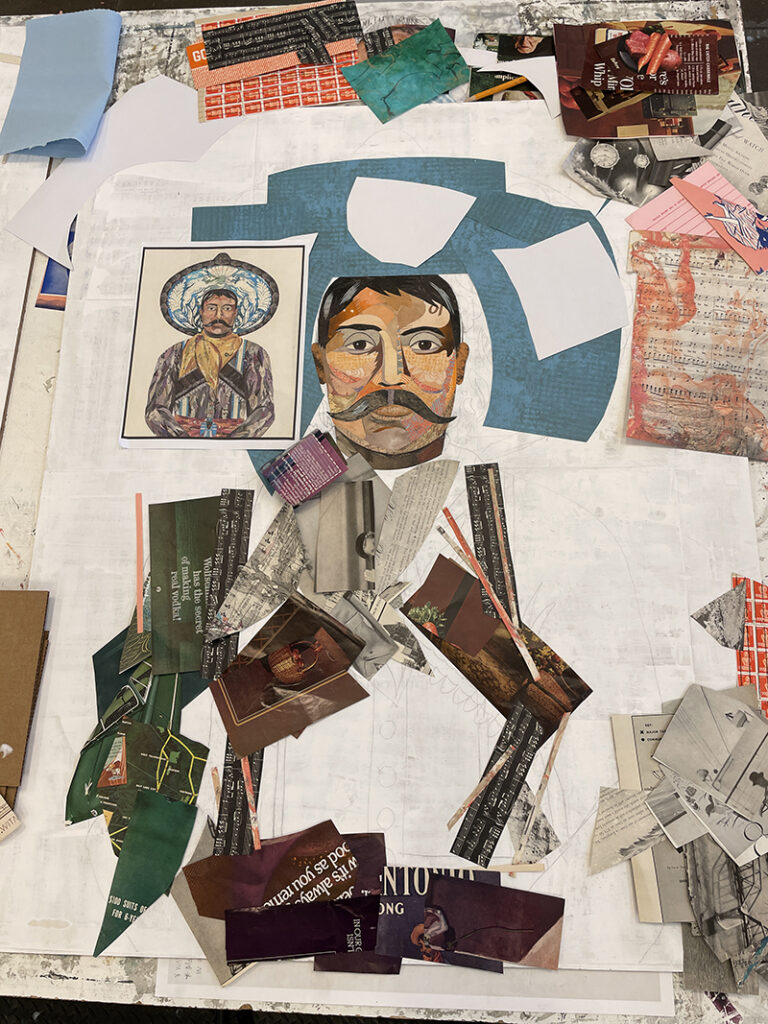

Most recently, Elliott commissioned Geiman to create two original works – one of Fredericksburg’s founder, John O. Meusebach, and the other of the Comanche Chief, Buffalo Hump, whom Meusebach negotiated the historic 1847 peace treaty with. The artist pulled from his massive collection of vintage papers – including Hill Country newspapers, building deeds, maps and old magazine advertisements – to complete the commission and pay homage to a defining moment in Texas history.

Projects like these were just two of Geiman’s recent works that demanded an elevated level of intricacy. “I found during Covid that there was this move to make work that was a little bit bolder and more detailed, because people were spending more time looking at things in their house,” he observes. “So, I was stepping up my game with the amount of detail I put in the pieces, and I found that people were really responding to that.” The months of lockdown also provided him ample time to reflect on his growing business. “I spent a lot of time just exploring better business practices or ways to really connect with my clients,” he says. “There was no off day, but I did get outside a lot more and would force myself to go take walks and find materials.”

While the trails were busier than normal, Geiman found his own solace and solitude in the Colorado wilderness. He and his wife moved to the Centennial State in 2015 after over a decade of living and working in Chicago. “Being able to grow up there as an artist was great, but I was really worn down and working crazy hours,” he explains. “We had been coming to Denver for art shows, so we moved and made it work; it is kind of like everything else I have done in my life – just make a decision and do it.”

These days, all of Geiman’s decisions are paying off and the artist’s client base is ever-growing, including a notable roster of high-profile corporations like YouTube, Microsoft, New Balance, and the Grande Ole Opry, to name a few. “We have various celebrities not to mention thousands of amazing clients all throughout the United States, but my heart is in Texas; that is where we really got our start with a lot of the larger pieces I created,” he says. In fact, a whopping 75% of his clients reside in the Lone Star State today.

“What is nice as an artist is, when I go to Texas, they don’t require me to sell the work,” he shares. “Texans look at it, appreciate it, and connect with it … they just get the aesthetic.”

Dolan Geiman’s portraits of John O. Meusebach and Comanche Chief Buffalo Hump portraits are available in the Hill Country exclusively at Black Chalk Laundry, 306 S. Lincoln St., in Fredericksburg. blackchalkhome.com